Potentially Bad Philosophy

Quietude might be described as as figuring out under what odd conditions it might be good to question some of our most trustworthy guides in philosophy and theology.

This is dangerous stuff, because we depend on those guides. We rely on their investment of (life)time, their investment of contentious discourse, and we take advantage of their brainpower. We stand on their shoulders. So when we choose to hop off their shoulders (or more commonly, hop onto another giant’s shoulders), we’d better have a good reason.

After we invest our trust in a person, concept (meme), or family of concepts (memeplex), it’s tough to make us leave. The speedbump we felt on the way “in” grows into a wall against going back “out.”

The feeling there is “incredulity.” As Manowar‘s 1987 heavy metal song “Carry On” claims, “100,000 riders! We can’t all be wrong!”

To keep incredulity in check, we ask, “When might even 100,000 heavy metal fans be wrong?” or more to the point, “When might dozens of brilliant philosophers be relying on fundamentally poor metaphysics?” What memetic “forces” could entrap even the otherwise trustworthy? When should we row against the current?

Viral Wildcards

We talked before about logical Wildcards. Any concept that has “vivid ambiguity” can be used, deliberately or not, to “bridge-make” (jump to conclusions that don’t really follow) and “bridge-break” (make legitimate conclusions seem like they don’t follow).

But this doesn’t just happen in isolated moments and stop there. Anything “useful” can stick and spread. This includes “Monkey’s Paw useful,” granting immediate wishes at a hidden, horrifying downstream cost.

Furthermore, that downstream cost may be “confusion, and the chatter it causes.” While we’d call this a “cost” in terms of what we consider praiseworthy and constructive, it is not a memetic cost, it is a memetic benefit.

That’s because this chatter boosts surfacing. It’s hard to hear Quiet folks.

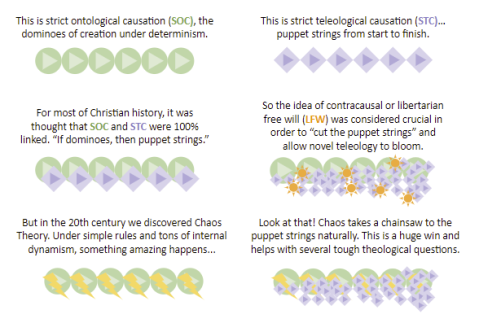

The rhetorical utility of vivid ambiguity, combined with its natural self-surfacing, becomes a Wildcard-fueled memetic engine:

A Potential Problem

An example of the above pattern may be the philosophical concept of Aristotelian potentiality.

I’ve said before that I don’t think it’s possible to confront Wildcards directly (see the bottom-right gray box, above). All we can do is consider alternatives and try them on for size. Last time we did this with metaethics. Today it’s potentiality.

We read in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

“… Another key Aristotelian distinction [is] that between potentiality (dunamis) and actuality (entelecheia or energeia)… a dunamis in this sense is not a thing’s power to produce a change but rather its capacity to be in a different and more completed state. Aristotle thinks that potentiality so understood is indefinable, claiming that the general idea can be grasped from a consideration of cases. Actuality is to potentiality, Aristotle tells us, as ‘someone waking is to someone sleeping, as someone seeing is to a sighted person with his eyes closed, as that which has been shaped out of some matter is to the matter from which it has been shaped.’

This last illustration is particularly illuminating. Consider, for example, a piece of wood, which can be carved or shaped into a table or into a bowl. In Aristotle’s terminology, the wood has (at least) two different potentialities, since it is potentially a table and also potentially a bowl.”

(I’m not going to summarize the above so you’ll have to read it.)

This Aristotelian perspective, whereby potentiality in a sense ‘lives’ within an object, is widespread in classical Christian theology and reverberates even in modern modal analytic philosophy. But I suspect it may just be a poor (but intuitive!) way of expressing prospective imagination. I’ll show you what I mean, and why the Aristotelian sense doesn’t fit nicely with a couple examples (which in turn expose the inconsistency of the language games we play).

I can look at a quarry and imagine the potential of building a cathedral using its stone. But if we allow the test of “potential or not” to include every other requirement for cathedral assembly (including laborers to work the quarry and adequate incentives to motivate them), then it doesn’t seem so natural to say that some rock formation has such potential, in isolation. It needs help. Reductively, nothing happens unless the universe helps, including all prior states of the universe up to that point, in a cosmic help-funnel of “efficacious Grace” concluding at that final capstone. This is not simply universal reliance on some Unmoved Mover; this is, “potentiality is not real.”

In other words, in a universe empty of sculptors, but replete with rocks, no rock has potential to be sculpted. It is only when we grant the antecedent “but if there were sculptors” that its potential suddenly “is there.”

This is not real stuff. Rather, potentiality is simply a roundabout, yet shorthand way of conjoining a fact or object X with a set of antecedents, imaginary or not, which as a group are sufficient for some consequent Y. And then we utter, “X has the potential for Y.”

Aristotelian Potentiality’s Payoff

Whenever widespread language and intuitive conceptualization is imprecise in this way, we’d expect a sensible explanation for it — a rational reason why the irrational description has memetic resilience and virulence (sticky and spready).

The answer is that we’re very sub-omniscient. We don’t know very many of the facts “God knows,” so to speak. And we therefore treat the unknowns as “possible worlds,” leaning on the “holodecks of our imaginations” to narrow the focus of our prospect-seeking. This helps us avoid the anxiety of “analysis paralysis,” which is handy because, of course, the early bird gets the worm.

It should be noted that well-developed spatiotemporal faculties may be a prerequisite for using this “visual” approach to handling evaluation of contingency and consistency given uncertainty. Some studies suggest that children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder, while just as capable as others in handling counterfactuals, take different strategies to evaluate them, preferring lists of facts and their contingent relationships vs. “holodeck stories.” However, as they age they acquire skill in both.

Aristotelian Potentiality’s Discomfiture

One way to expose the irrealism of Aristotelian potential is to apply it to that which is real and closed, and find it doing conflicting things; examples where it clearly “ain’t right.”

“Sea Peoples Potential”

Consider the sentence, “The Sea Peoples who invaded Egypt in the 12th century B.C. could’ve been Aegeans.” We say “could’ve” here when we know the answer is fixed, but simply unknown. And therefore there’s a sense of “potentiality” even when it’s obvious the Sea Peoples have already come and gone, and were who-they-were.

“Fallen Coin Potential”

Another example is, “The coin could‘ve landed tails, but it landed heads.” We say “could’ve” here, and retrospectively invoke the sense of potentiality we felt 5 seconds ago, prior to the flip, when the result was unknown, and therefore probabilistic. We say this even though the result of the flip was deterministic, the fixed result of chunky kinetic forces* we humans have trouble tracking.

Put another way: “Deterministic results couldn’t be other than what they were; so why/when do we give them probabilities anyway? How on Earth do we get away with saying both ‘couldn’t’ and ‘could’ve’ about them?” These questions now have simple answers.

* (If needed, imagine the coin flip in a virtual simulated environment, to control for “quantum” or “free will” factors.)

Conclusion

I affirm the finding of a number of early 20th century philosophers that metaphysics comes down to language. It’s often buggy. These bugs sometimes foster tiny, sneaky non sequiturs that let astounding conclusions pop forth. Unless trained against these, even brilliant people are more likely to shout “Eureka!” than “Error!”

This phenomenon creates a memetic incentive to unknowingly exploit, and tendency to inherit, buggy metaphysical concepts (because we trust tradition and the brilliant, renowned people who pass it along). I suspect Aristotelian potentiality is such a thing.

Further Reading

- To explore how open language is compatible with a closed past, present, and future, read “Schrödinger’s Cup: A Closed Future of Possibilities.”

Please Stop Saying Free Will Contradicts Universal Reconciliation

There’s a meme that universal reconciliation (wherein the Gehenna of Judgment doesn’t last forever) doesn’t work with free will (or agency, or dignity, or cooperation, or what have you).

We’ve discussed this before on this blog, but that material had some distractions that I hope we can avoid this time around.

The point this time is to focus, and make a really simple rebuttal of the idea that these two things are incompatible.

In order to focus, we’re going to avoid defining free will — whether you think it’s the libertarian kind, or a compatibilistic kind, or something else, should be unimportant to the argument.

(The argument is pointing out a non sequitur — “Free will’s falsity is not a corollary of purgatorial universal reconciliation, and PUR’s falsity is not a corollary of free will” — by way of a thought experiment.)

The Three Humans

Imagine that there are only 3 humans: John, George, and Ringo.

Here are 3 possibilities:

- In possibility 1, only John shall freely submit to God at Judgment, and George/Ringo shall remain in rebellion.

– - In possibility 2, both John and George shall freely submit to God at Judgment, but Ringo shall remain in rebellion.

– - In possibility 3, all three of John, George, and Ringo shall freely submit to God at Judgment.

We don’t have to commit to any of these possibilities, but can talk about a series of “ifs” related to possibility 3.

In other words, let’s “float” possibility 3 for a moment, and see what happens:

- If possibility 3 happens, there’s no contradiction between possibility 3 and free will, since all three humans in the group freely submitted.

– - Furthermore, if God knows that possibility 3 shall come about, there still shouldn’t be any contradiction with free will.

- (God knowing something does not have any effect on the group’s free will.)

–

- (God knowing something does not have any effect on the group’s free will.)

- Furthermore, if God inspires a writer to assert that possibility 3 shall come about, there still shouldn’t be any contradiction with free will.

- (God inspiring a writer to make that assertion does not offend the group’s free will.)

–

- (God inspiring a writer to make that assertion does not offend the group’s free will.)

- Furthermore, if folks read those assertions and subsequently believe with confidence that possibility 3 shall come about, there still shouldn’t be any contradiction with free will.

- (Folks holding to a conveyed foretelling with confidence does not offend the group’s free will.)

All done.

All across the board, John, George, and Ringo’s free wills have not been offended in any way, even if possibility 3 is held true for the sake of argument. This hypothetical premise simply isn’t catastrophic to freedom, dignity, agency, and whatnot. Everything’s fine.

Conclusion

PUR may be false. Perhaps some will refuse to submit at Judgment, and opt for interminable rebellion instead.

But the truth or falsity of PUR is not presently at issue.

Rather, at issue is the meme, “PUR would contradict free will if it were true.”

And that meme is false. It entails non sequiturs.

Incredulity

How can it be that the above meme is so virulent and resilient, even among very educated, sincere, brilliant thinkers?

The reason is because non sequiturs are extremely difficult to root-out, especially when they involve tough-to-crack concepts like free will.

I suspect that a modal scope fallacy is responsible for this non sequitur. Modal scope fallacies are very, very easy to commit, even from people vastly more intelligent than you or me.

Visit the Purgatorial Hell FAQ and search the page for “free will” to look deeper into the modal scope fallacy we often see here.

Determinism Doesn’t Mean a Micromanaging God

“Durdle Dwarves” is a simulation where little “Dwarf” pixels dig-through and build rock-like structures. They do this according to a set of 20 rules. A rule tests a Dwarf’s vicinity and provides a response. (For example, if a Dwarf notices a drop-off to his left, he’ll build a new piece of “bridge”; that’s 1 rule of the 20.)

The simulation is 100% deterministic, and the state of the world at a certain time is a strict function of those initial rules, plus the starting state.

For instance, this starting state:

Yields this world state after 13,500 ticks:

Let’s pretend we don’t like something about this result. Perhaps that structure just below the middle — the one that looks a bit like a road with a lane divider — displeases us.

We could just pause the simulation and erase it, of course.

Because we have the arbitrary power to change things at any time, you and I are sovereign over this world.

But each interruption like this comes at a cost. Even though we were displeased by the road-like shape, we’re also displeased to intrude upon the natural flow of events. In our set of innate interests, one interest is that the world have as few of these intrusions as feasible.

Another option is to change the starting state of the world. Let’s make our initial two “Adam & Eve Dwarves” one block farther apart.

And here’s what things look like after 13,500 ticks:

Hooray! We got rid of that nasty road-like pattern.

But there was a cost here, too. The world is dramatically different now. Here’s the “Before & After”:

This kind of thing is nicknamed the “Butterfly Effect” in chaos theory. The tiniest of changes, over time, produces explosive world differences in nonlinear and/or interactive systems.

This is irritating, too, because we liked the world basically how it was, we just didn’t like the road pattern. Now everything is way, way different.

How annoying!

Let’s define micromanagement as, “Controlling things with surgical precision.” Is there a way to micromanage-away that road, so that we keep the rest (through our precise surgery), but also without using the blunt force of the eraser?

You might be thinking, “Why don’t we alter the starting rules, so that the road never appears?”

Unfortunately, merely altering one of the 20 core rules, or adding just a few rules, has the same explosive “Butterfly Effect” that dramatically changes the world state at frame 13,500. So, this would fail to micromanage.

As it turns out, the only way to pull this off is to have tons and tons and tons of core rules.

And this, of course, has the cost of being horribly ugly and inelegant.

Some folks would tolerate that inelegance. But you and I agree that this basically defeats the point of creating these guys at all. We take pleasure — let’s say — in the emergence of these forms out of an elegant, simple foundation.

Where This Leaves Us

“Durdle Dwarves” is just a computer program.

However, it’s such an obvious deterministic cloister that it serves as the “worst case” for verifying whether determinism always means full micromanagement.

The answer? It doesn’t.

If we have an innate interest in maintaining systemic elegance, then the degree to which the world is micromanaged is equal to the degree to which we have found it warranted, in certain rare circumstances, to intrude, even as we’d rather not intrude.

Notice that our innate interests have what’s called “circumstantial incommensurability” at the “13,500 circumstance.”

It’s not power-weakness that makes a wholly-satisfying solution impossible. Remember, we’re 100% powerful over that world.

Rather, a wholly-satisfying solution is arithmetic nonsense.

What This Shows Us

An entity can be 100% sovereign and powerful over an interactive deterministic world, including that world’s core rules, starting state, and modifications to any subsequent state.

But if that entity has innate interests in an elegant ruleset, then the world is not necessarily micromanaged. Then, if the entity never intrudes, then the world is not micromanaged at all. And if the entity intrudes to some limited degree, then the world is micromanaged only to that degree.

Primary Causation & Secondary Causation

If we start with an elegant core ruleset in a sizeable interactive system, then as time goes on, I will lose surgical control over that system, even if I’m 100% sovereign over it.

True, but pretty dang counterintuitive.

It is only when I find it justifiable to intrude that I can wrest-back some amount of surgical control, temporarily.

- The reductive perspective is that since these decisions are all “up to me,” everything in the system reduces to “my causation.”

–

This is the perspective from which St. Irenaeus wrote in the 2nd century, “The will and the energy of God is the effective and foreseeing cause of every time and place and age, and of every nature.”

But this fails to capture something important to me, doesn’t it? Indeed, a formative perspective is needed to capture my interests.

- The formative perspective is that there is a meaningful — according to my interests — difference between primary causation, the stuff that glows brightly with my exceptional exertions of power, and secondary causation, the “teleologically-dimmer” stuff that starts to act weirder and weirder as time goes on.

–

This is the perspective whereby we rightly deny that God “authors” sin under chaotic determinism; rather, he broadly suffers it.

These two perspectives are simultaneously true in heterophroneo (a concept we’ve been exploring on this site that’s similar to Aristotle’s hylomorphism, but not exactly).

Conclusions

- Those who say “under determinism, primary and secondary causation have no meaningful distinction” are mistaken.

– - Those who say “under determinism, a sovereign entity has 100% micromanagement, irrespective of that entity’s interests” are mistaken.

Please see last year’s article, “The Sun Also Rises,” to explore other philosophical and theological puzzles that “form heterophroneo” finally puts to bed.

Explore “Durdle Dwarves” for yourself here. Press “Start” to see the world erupt chaotically but deterministically, according to a small set of rules.

Short and sharable:

Schrödinger’s Cup: A Closed Future of Possibilities

Adequate determinism (or determinism for short) is the idea that on the level of human decisionmaking, history flows into the future in a deterministic way — there aren’t really multiple futures, but we talk and imagine as if there are.

Because we talk and imagine as if there are really multiple futures, confronting an assertion of determinism often yields Kochab’s Errors, where folks think that determinism fundamentally “changes” things and destroys all sorts of stuff we value.

With determinism, the fear is typically that we lose morality, choice, volition, agency, efficacy, and free will. This fear is called “incompatibilism” — where one believes that our treasured “volitional dictionary” is not compatible with determinism.

Incompatibilism usually prompts people to reject determinism, but there are deterministic incompatibilists as well, like atheist Sam Harris. Indeed, for some this isn’t a fear, but something to accept with open arms.

Compatibilism, by contrast, is a semantic response to determinism that avoids Kochab’s Errors, remembering that the world remains just as it was, but commits to a refined edition of the “volitional dictionary” when speaking philosophy and theology with precision.

Compatibilism is exciting because — though it’s a bit mind-bending at first — it yields more robust, coherent, and resilient philosophy (especially with regard to meta-ethics), but also a theology under Christianity that finally proclaims both human choicemaking and God’s exhaustive sovereignty. We assert that the Bible is compatibilistic by means of “heterophroneo.”

The Open Future

No matter which position we hold, we all nevertheless use open language to talk about the future.

Consider the diagram below.

Before me is a choice between two mutually-exclusive options. One option will yield “Future A,” and the other “Future !A.”

This seems pretty intuitive. The past is on the left, and the future possibilities on the right.

Only one problem, though. Those futures are colored the full black of “reality,” as real as “Me Right Now.”

But we know this cannot be. They have not yet been “real-ized.” In other words, they’re not “act-ual” because nothing has “acted” them yet.

The simple answer is that these prospects aren’t floating around in the future, but floating around in my mind.

We who have well-developed neocortices can very vividly project, using our imaginations, possible futures. This is very useful to us, because we can “see future worlds” as concepts and pictures rather than being burdened to forecast detail after detail. This generally helps us make better decisions more quickly (to a point).

But still, we’re seeing these prospects as full black. Even though we’ve done the correct thing by encasing these prospects where they truly live — our minds — we haven’t accounted for the fact that these things are mutually exclusive. If one happens, the other cannot, and so even in our brains, they should not simultaneously be full black.

Rather, they should be faded according to their plausibility.

If they’re each about 50% plausible, like a coin-flip, then we could imagine them as 50% ghostly:

It’s very important, however, to note that we don’t intuitively take this step.

Equally plausible options — especially arbitrary decisions, such as whether to get seconds at a potluck — tend to stay fully black in our minds. This quirk is so stubborn that we commonly employ language about these being “real possibilities” even though we know they’re doubly non-real: (1) They’re mutually exclusive, and so cannot be simultaneously real, and (2) they’re in our minds (not yet “real-ized”).

Seeking precision with quietude would have us admit that we use “real” as a nickname to describe prospects that are simply “plausible,” “appreciable,” “real-istic,” etc.

Now consider when one prospect is extremely implausible:

Here, we say things like, “Future !A isn’t a real option,” because we see it as so difficult or otherwise unlikely.

This includes unlikely prospects about behavior that I’d never see myself doing. If someone asked me, “Could you strike your partner?” I’d quickly shout, “No, never!” This isn’t because I lack arms or motor functions therein, but because that prospect is so un-real-istic.

The Open Past

Just as we use open language to talk about the future, we use open language to talk about the past (and the present, which for our purposes is a part of the past, that is, it is the immediate past).

It’s true!

Even though we know the past is closed, we still use open language to talk about the past. Isn’t that strange?

So, when do we do this?

We do this when we’re uncertain about the past.

Put a coin in a cup, shake it around, and slam the cup onto the table.

You can see just enough that you know the coin has fallen. But the cup is just opaque enough that you can’t tell whether it’s fallen heads or tails.

Let’s call heads “Fact A” and tails “Fact !A”:

Because I cannot ascertain the result, the most I can do is imagine the two possibilities. It may be heads, but it may be tails. It certainly can’t be both.

But look! I just talked about possibilities. I talked about what “may be the case”; I’m not talking not talking about a future reveal — perhaps I never plan to peek — but talking about what was and is currently the case, using the word may.

That’s open language!

We don’t just do this with the coin/cup game — (everyone’s favorite pastime) — but with any past-or-present thing of which we’re uncertain:

- “Is Harriet already at the restaurant?”

“It’s possible. But maybe she got held up.”

– - “I don’t know what the bug in the code is. It’s possible that it’s a null pointer exception.”

– - “Did you remember to feed the dog today?”

“For the life of me, I can’t remember. It’s possible I forgot.”

– - “I didn’t speak to George before he left for vacation. Did he get those e-mails sent?”

“Possibly. I saw him hurrying to get something done.”

– - “Did God use some degree of evolution to yield the diversity of life we see on Earth today?”

“Possibly.”

– - “It’s possible that some supposed Apostolic martyrdoms are legends that didn’t actually occur. We don’t know for sure.”

– - “Is Janice a double agent?”

“Possibly! We’ll need to keep an eye out to find out.”

See?

Open language is a function of uncertainty — it is not at all evidence for the simultaneous reality of mutually-exclusive prospects.

Open Language as Strategy

I.

Little David’s birthday is coming up, and you’ve told him that you plan to give him a present.

“What is it?” David asks. David is ignorant, that is, he does not know what the gift shall be.

“It’s something from your birthday list,” you say, “but it needs to be a surprise. I’ll tell you this: It could be a skateboard, a video game, or a jacket.”

You’ve already bought David’s gift. It’s definitely a skateboard. But it suits your goals to use open language with David nonetheless.

II.

Later that year, you’ve planned a vacation at a famous theme park. Airfare, hotel, tickets, etc. have all been booked.

The night before the flight, David’s behavior is out of control. You make the following threat, “If you don’t behave immediately, David, we will not be flying anywhere tomorrow. I will not be rewarding this behavior.”

You know for sure that this will be compelling. You know for sure that you’ll be flying tomorrow. These are closed facts for you.

But the hypothetical conditional remains true; if he didn’t behave, there would be no flight. You weren’t lying about that.

This is because true conditionals can have false — even knowingly false — antecedents.

In other words:

- You can be a truth-teller,

– - and convey a contingency using open language,

– - while simultaneously knowing the falsity of the antecedent and what tomorrow’s outcome shall be.

And why would you do this? To get David to clean up his act; to meet your goals (including sanity) and his (like a long-game interest in self-control).

III.

For a couple more examples, you could tell David, “If you don’t finish your chores today, then we won’t go to the movies tonight,” even if you know for certain that he’ll finish his chores; it may even be that obedience is contingent upon hearing that threat, which you know.

Or, you could tell him, “If you don’t finish your chores today, then we won’t go to the movies tonight,” even if you know for certain that he won’t. You could do this as a sort of investment to further prove that your “threats have teeth”; that is, you consistently follow-through with the punishments you threaten.

Conclusion

Open language does not at all suggest that multiple mutually-exclusive things can all be “real.” It is not a “gotcha” vs. determinism. We use open language with past facts which are commonly regarded as closed.

Furthermore, a person can honestly and productively use open language with regard to certain events even if that person knows the facts of those events in a closed way. That person can nevertheless employ “maybes” and other hypothetical statements, and this communication strategy can be very useful for interaction and relationship.

As such, whether or not determinism is true, we can say confidently that determinism is compatible with the common and purposeful use of open language about the future.

Further Reading

One can be a Christian deterministic compatibilist without becoming a Calvinist; Calvinism entails several further assertions, and I am not a Calvinist.

- “Freedom & Sovereignty: The Heterophroneo.”

A primer on the Biblical compatibilist solution.

– - “Jumping Ships from Open Theism to Compatibilism.”

Ten challenges for Open Theism (or “Open Futurism”), and why compatibilism ought be adopted instead.

– - “Libertarian Free Will is a Poweful Meme, Whether or Not It’s True.”

How our feelings of spontaneity and “prospect realism” turn into a virulent, resilient meme.

Purgatorial Hell FAQ

Welcome to the Purgatorial Hell FAQ.

This is a tour through the issues and questions related to hell’s duration being finite rather than infinite.

It isn’t absolutely comprehensive, but I hope this is dense enough that you’ll feel that the case is made and that your questions have answers. If you have any corrections, insight, or additional questions, feel free to comment below.

Format:

Q: Question.

A: Main answer. Other details and bonus information. My own opinions on some matters.

It’s meant to be read as an article, but you can use it for reference later on.

Q: What is purgatorialism?

A: Purgatorialism is the view that hell is purgatorial (“pur” is Greek for “fire”). Hell is measured in equity according to what a person did, and is for a remedial (healing/surgical) purpose.

It is agonizing and humiliating and we should fear it, and the Good News is, in part, that we can be forgiven and avoid the wrath we’d otherwise bear.

Q: What other names does it go by?

A: It’s also called purgatorial universal reconciliation (“PUR” for short) because the end result is God’s stated master plan in Ephesians 1:8b-10:

“With all wisdom and understanding, he made known to us the mystery of his will according to his good pleasure, which he purposed in Christ, to be put into effect when the times reach their fulfillment: To bring unity to all things in heaven and on earth under Christ.”

Even though this relates specifically to the duration and nature and purpose of hell, much of Christian theology (God’s character, nature, purposes, plans, ways, and our worldview and mission methodology) is influenced by the kind of hell we believe in. The theology that proceeds from hell being finite rather than infinite is “PUR theology.”

Q: What are some related names/labels I should be aware of?

A: PUR stands in contrast to “no-punishment universalism,” the idea that the threats of God’s hellish wrath were just scare tactics and exaggerations, and — surprise! — everyone will be saved from their due punishment. This “no punishment” view — “NPUR” — cannot be reconciled with Scripture and was not believed among early Christians.

“Christian Universalism” is an attempt to differentiate universalist eschatology from the non-Christian denomination, “Unitarian Universalism.” It doesn’t go far enough, however, because a Christian Universalist may still espouse NPUR.

“Evangelical Universalism” or “EU” is sometimes used to preclude NPUR, since some folks use “Evangelical” as an idiom for a “Bible-first” heuristic. I assert this is mostly confusing, however, since “Evangelicalism” implies all sorts of unrelated things.

Q: Was it believed among early Christians?

A: Yes. It was one of the “big three” views of hell that we find in early Christian texts, even taught by orthodox Christian saints.

Those “big three” views were:

- Annihilationism. Either the unsaved are never resurrected, or there is a general resurrection and Judgment, where the saved are found in the Book of Life, and the unsaved undergo suffering, and obliterated (Arnobius, St. Ignatius of Antioch).

– - Endless hell. There is a general resurrection and Judgment, where the saved are found in the Book of Life, and the unsaved undergo suffering forever (Tertullian, Athenagoras, St. Basil the Great).

– - Purgatorial hell. There is a general resurrection and Judgment, where the saved are found in the Book of Life, and the unsaved undergo punishment measured in equity according to what a person did, and are ultimately reconciled, but through dishonor and shame, like being procured from the dross (St. Clement of Alexandria, Origen Adamantius, St. Gregory of Nyssa).

Q: Which of the “big three” views was prevalent?

A: We don’t know.

Annihilationists like to say it was annihilation. Endless hell believers like to say it was endless hell. Purgatorialists like to say it was purgatorial hell.

But we don’t really know. Complications:

- Writings from all three camps used the same Biblical language to support their view. For example, St. Irenaeus, St. Gregory of Nyssa, and St. Basil the Great would all three say that the unsaved shall suffer the kolasin aionion (the punishment-of-ages). As such, we can’t depend on such language to support any specific camp unless a writer also makes statements that further clarify their position. And many did not do this.

– - Even if all such writings were 100% unambiguous, the plurality of supporting writings does not indicate plurality of early supporters.

– - Further, plurality of existent supporting writings is an even worse indicator, since writings were, at various lamentable times, subject to selective destruction as it suited church authorities (this isn’t a conspiracy theory, but a benign fact that complicates our search).

– - And, of course, there’s the nagging fact that popularity does not entail veracity (truth/falsehood). It’s just an okay heuristic.

Q: Which of the “big three” views eventually prevailed?

A: Endless hell, of course! This happened in the 5th century, largely due to the influence of St. Augustine, a full-on Christian celebrity-theologian of his day.

St. Augustine considered it one of his missions to convince the Christian purgatorialists of endless hell, and entered into the “friendly debate” (City of God). As an endless hell believer, he’s our best “statistician” on this issue, since he admitted in Enchiridion that, in his day, there were a “great many” Christians that believed hell was purgatorial.

St. Augustine is largely responsible for the turn toward endless hell dominance in the church: He was eloquent, prolific, assertive, and creative.

Q: What are the “impasses” that divide the “big three”?

A: The “big three” cannot agree on how to interpret Gr. apoleia / apololos and Gr. aion / aionios /aionion.

The first word family is variously translated as “perishing,” “destruction,” “lost”-ness, and “cutting-off.” Annihilationists would prefer to take these literally and at face-value when possible. Those who believe in experiential hell (purgatorial hell and endless hell) say that everyone will receive perpetuity (“lingering forever”), and so these words should be taken in the sense of “lost-ness” and “cutting-off.” Purgatorialists would then say that even those lost and cut-off are salvageable, like Luke 15’s “lost (apololos) son” and “lost (apolesa) coin.”

The second word family is variously translated as “age,” “of ages,” “of the age,” “eternal,” and “everlasting.” Those who believe in an interminable doom (annihilation and endless hell) say that “eternal” and “everlasting” are good translations of these words when pertaining to the fate of the unsaved. Purgatorialists counter that such assertions are reckless and imprudent: According to the ancient lexicographers these words mean only “age-pertaining” and do not speak for the duration, but only that their duration and/or place in time is significant.

Q: So… who’s right?

A: Purgatorialists. (At least, that’s how a purgatorialist would answer!)

The Positive Case for Purgatorial Hell

Q: Enough history! Does it say in the Bible that everyone will be reconciled?

A: Yes, in Romans 11. Romans 8:18 through 11:36 is a prophetic theodicy that ends with the “upshot” of universal reconciliation.

A “theodicy” is a rationalization of some “bad thing” in terms of its being ancillary (useful and necessary as part of an optimal plan). There are experiential theodicies (specific rationalizations of specific sufferings) and abstract theodicies (showing how bad stuff could be rationalized in theory; that is, we can maintain a non-deluded hope in rationalization).

For most of us, experiential theodicy is above our paygrade. But if you’re a prophet or otherwise divinely inspired, you can be given the Grace to reveal a specific experiential theodicy.

It goes something like this:

- Admit a bad thing and lament over it.

- Postulate different ways to frame the bad thing, some of which make it more understandable.

- Appeal to God’s sovereignty over the good stuff and bad stuff.

- Postulate a reason for the bad stuff. If you’ve got guts, assert a reason for the bad stuff.

- Assert how the bad stuff is temporary.

- Assert the happy upshot with praise and thanksgiving.

- Shout God’s praises, shout the mystery of his plans, then fall flat on the floor in exhaustion.

In this case, the “bad thing” is the fact that, in Paul’s day, very few of his kin — “familiar Israel” — were recognizing Christ as the Messiah (9:2). He lamented it, even such that he’d sacrifice himself to make this bad thing not the case (9:3).

He postulates a different way to think about the bad thing; that there is a new, “spiritual” Israel of God’s elect, and so in a sense, all Israel (in this sense) has signed-on (9:6). But Paul soon returns to the discussion of regular, “familiar” Israel (9:24+, 31).

He appeals to God’s sovereignty over the good stuff and bad stuff (9:11-18), even to the degree that one might complain about God’s will being superceding over human will (9:19). But Paul holds his ground (9:20-21).

He then asserts a reason for this bad thing: The stumbling of familiar Israel is ancillary to bring in the Gentiles, who will (in turn) provoke a legitimate jealousy that will eventually bring in familiar Israel (11:11-12).

“Coming in” is contingent upon belief, but all will eventually believe. We know this because Paul says the “pleroma” will be reconciled.

Pleroma means overfull abundance, of such excess that it was used as an idiom for patched clothing. Some ultra-important theological pleromas in Scripture:

- “The Earth is the Lord’s, and the pleroma in it.” (1 Corinthians 10:26)

God is sovereign and owns absolutely everything.

– - “Whatever commands there may be are summed up in this one command: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself’ Love does no harm to a neighbor, therefore love is the pleroma of the law.” (Romans 13:9b-10)

Love completely fulfills the law under the New Covenant.

– - “For in Christ is the pleroma of the Deity, bodily.” (Colossians 2:9)

In the Trinity, Jesus Christ is full-on God, not some lesser being.

See how important pleroma is for orthodoxy?

Paul explicitly says that the elect are not the only ones with hope — the hope of reconciliation awaits even those who are not elect:

“What the people of Israel sought so earnestly they did not obtain. The elect among them did, but the others were hardened… Again I ask: Did they stumble so as to fall beyond recovery? Not at all! Rather, because of their transgression, salvation has come to the Gentiles to make Israel envious. But if their transgression means riches for the world, and their loss means riches for the Gentiles, how much greater riches will the pleroma of them bring!”

Is reconciliation for nonbelievers? Nope:

“Consider therefore the kindness and sternness of God: sternness to those who fell, but kindness to you, provided that you continue in his kindness. Otherwise, you also will be cut off (11:22).”

But is the cutting-off a sealed end? Nope:

“And if they do not persist in unbelief, they will be grafted in, for God is able to graft them in again (11:23).”

Paul wants to be clear, here. He does not want us to be “ignorant of this mystery” else we might get conceited — like Jonah or the Prodigal Son’s brother — about our “specialness” vs. the for-now hold-outs:

“I do not want you to be ignorant of this mystery, brothers and sisters, so that you may not be conceited: Israel has experienced a hardening in part until the pleroma of the Gentiles has come in, and in this way all Israel will be saved (11:25-26a).”

The ancillary purpose to God’s deliberate election and stumbling:

“Just as you who were at one time disobedient to God have now received mercy as a result of their disobedience, so they too have now become disobedient in order that they too may now receive mercy as a result of God’s mercy to you (11:30-31).”

The upshot:

“For God has bound everyone over to disobedience so that he may have mercy on them all (11:32).”

The shout:

“Oh, the depth of the riches of the wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable his judgments, and his paths beyond tracing out! Who has known the mind of the Lord? Or who has been his counselor? (11:33-34)”

Q: The pleroma stuff aside, what if some people persist in endless rebellion and refuse to confess?

A: Romans 14 says that won’t happen. Romans 14:10b-11 says, “We will all stand before God’s Judgment seat. It is written: ‘As surely as I live, says the Lord, every knee will bow before me; every tongue will fully confess to God.'”

- “Every knee will bow” is full submission. It is implausible that anyone will submit to God Himself and then pop back into rebellion like a jack-in-the-box.

– - “Every tongue will fully confess” is full confession, Gr. exomologo-. This is the attitude of those who repented and were baptized by John (“Confessing their sins, they were baptized by him in the Jordan River” Matthew 3:6) and those who heeded James’s admonishment (“Therefore, confess your sins to one another and pray for each other” James 5:16a).

This does not match with the idea of “endless rebellion” to justify endless hell or “incorrigible rebellion” to justify annihilation.

As such, some have said that Judgment at this “phase” is limited to the saved. Indeed, the context of Romans 14 is against intolerant believers. But Paul’s quoted passage from Isaiah continues: “All who have raged against him will come to him and be put to shame.”

And here it must be noted that the above idea is not found in Scripture. It was invented centuries later, “post hoc” (that is, after the “need” for such conjecture arose). So this isn’t a matter of dueling prooftexts; “endlessly-incorrigible people” lacks Scriptural warrant. Scripture instead says everyone will bend the knee, “as surely as God lives.”

The conclusion, we assert, is rock-solid: The pleroma will be reconciled, some after a cutting-off and shameful submission. The Good News is that we don’t have to be in that shamed group, and can become implements of honor, knowing God through Christ Jesus right away in the zoen aionion of the Kingdom of God.

Q: Doesn’t this, then, contradict free will?

A: No. Promises about the eventual willful submission and full confession of all people do not oppress anyone in any meaningful way. All will volunteer this submission and full confession.

The idea that such promises invalidate free will comes from a thing called the “modal scope fallacy” (in this case, one driven by an upstream composition fallacy), which very often pops out of certain ideas of free will that are ill-defined or incoherent.

Here’s a thought experiment to help explain the modal scope fallacy at play.

Let’s say there’s a 5 x 5 board containing 25 light bulbs. Each bulb can be either off, or red, or green.

Every 1 second, the whole board lights up. For each bulb, it has a 50% chance of being red and a 50% chance of being green. Then, the board shuts off again.

A bulb’s random chance to be one color or the other we can call “light bulb randomness,” or “LBR.”

Here are three board states over 3 seconds:

Seems pretty random, right? If I told you that there was LBR here, you wouldn’t complain.

But what if I said that this board showed up eventually:

Here George might say, “How could LBR still be true, here? This doesn’t look random at all; all the bulbs are the same color.”

This is an example of a modal scope fallacy. LBR is about individual bulbs. LBR doesn’t mean that the board has to look random. LBR isn’t about the board as a group. Probability dictates that it would take about a year, but we’d eventually expect all light bulbs to be the same color at least once. And if we “froze” a bulb whenever it turned green, it would take only a few seconds.

Now, this is not to say that free choices are random. This is just to show how easy it is to commit a modal scope fallacy when we’re not careful to avoid it. It’s a fallacy even some very brilliant thinkers commit.

LBR isn’t about the lightbulbs as a group, and neither is free will about humanity as a group. It’s about individual choicemaking. Free will is not at all infringed even if all individuals make the same choice eventually. And it shouldn’t matter which definition of “free will” you use.

Q: Where, though, is hell described as purgatorial?

A: 1 Corinthians 3:15-17. The context is Paul lambasting a certain group of believers who were lazy and failing to build on their initial confession — the foundation of Jesus Christ, laid down for them by Paul as “foundation-builder.”

Paul makes an eschatological threat against these believers. (We could say “so-called” believers with an failing faith; “I gave you milk, not solid food, for you were not yet ready for it. Indeed, you are still not ready. You are still worldly. … I am writing this not to shame you but to warn you as my dear children.”)

At Judgment, the bad builders are in for a bad time.

The “bad time” they’re in for:

- They’ll “suffer loss,” Gr. zemio-. “What does it profit a man to gain the whole world, but himself being lost (Gr. apolesas) or suffering loss (Gr. zemiotheis)?” That specific disownment, in the context of Luke, is the same kind threatened in Matthew 10:32-33.

– - Their “lazy servanthood” parallels that of the gold-burier of Jesus’s parable: “And throw that worthless servant outside, into the darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth” (Matthew 25:30).

In other words, this isn’t just a “tut-tutting.” This is agony and humiliation. Disownment. And the result is the Gehenna hell of Judgment (see Matthew 10:28, the cost of disownment). A deconstruction by fire, the record exposed, and the shoddy works set ablaze.

But.

The sufferer is eventually rescued. Verse 15: “But he himself shall be saved, though only as through fire.”

(It’s, of course, possible to dispute that this is about the hell of Judgment, which is the proposal on deck. But it’s not possible to dispute that this is a real threat of real loss and yet real reconciliation, which supplies a reductio ad absurdum against those who think a pre-reconciliation agony is “meaningless.”)

Q: This is confusing. The unsaved shall be saved?

A: It can be confusing because there are many senses of salvation in Scripture. This is commonly recognized by all theologians, from all three “camps.” For every kind of trouble — whether spiritual or eschatological or physical and mundane — there is a Gr. soterios “from it.”

Usually, when we say salvation, we refer to “salvation from due wrath” which also entails salvation from sin in life (through forgiveness) and from the sinful nature in life (through sanctification). And that’s usually the sense meant by “salvation” by the New Testament writers and it’s the salvation to which believers in Christ have exclusive claim.

But there is a further sense of “salvation from ultimate ‘lost-ness.'” It is a rescue from unreconciliation that everyone will eventually experience, whether or not they were saved/unsaved (in the traditional sense).

As such, these passages give us the complete Pauline eschatology. Reconciliation is contingent upon submission and confession. Everyone will eventually submit and confess. The unsaved, at Judgment, will come in shame, and will be rescued, but only as through the purging fire of wrath (which we’d much rather avoid).

St. Clement of Alexandria puts it this way, in his commentary fragment on 1 John 2:2, from the late 2nd century:

“And not only for our sins,’ — that is for those of the faithful, — is the Lord the propitiator, does he say, ‘but also for the whole world.’ He, indeed, rescues all; but some, converting them by punishments; others, however, who follow voluntarily with dignity of honor; so ‘that every knee should bow to Him, of things in heaven, and things on earth, and things under the earth.”

Q: So, Ephesians 1, Romans 11, Romans 14, 1 Corinthians 3, and 1 John 2. Any other places where an ultimate reconciliation is promised?

A: Yes. The Bible repeatedly talks of God’s in-time desire that all be saved from sin and wrath, and God’s ultimate desire that all be reconciled.

Colossians 1:15-20

“The Son is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn over all creation. For in him all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or powers or rulers or authorities; all things have been created through him and for him. He is before all things, and in him all things hold together. And he is the head of the body, the church; he is the beginning and the firstborn from among the dead, so that in everything he might have the supremacy. For God was pleased to have all his fullness [pleroma] dwell in him, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven, by making peace through his blood, shed on the cross.”

1 Timothy 2:1-6

“I urge, then, first of all, that petitions, prayers, intercession and thanksgiving be made for all people — for kings and all those in authority — that we may live peaceful and quiet lives in all godliness and holiness. This is good, and pleases God our Savior, who wants all people to be saved and to come to a knowledge of the truth. For there is one God and one mediator between God and mankind, the man Christ Jesus, who gave himself as a ransom for all people. This has now been witnessed to at the proper time.”

1 Timothy 4:10

For it is for this we labor and strive, because we have fixed our hope on the living God, who is the Savior of all men, especially of believers.

“Especially,” Gr. malista, really does mean “especially” and not “only.” See Galatians 6:10, 1 Timothy 5:8, 1 Timothy 5:17, and Titus 1:10. Paul’s letter to Timothy is consonant with Paul’s eschatology: Everyone will be saved, but believers especially so, since they’ll receive all senses of salvation, i.e., not just the ultimate reconciliation, but salvation from wrath at Judgment.

Q: Do some PUR believers cite verses that don’t strongly support PUR?

A: Yes. Some passages look at first glance to be about an ultimate reconciliation, but are actually about the earlier, exclusive salvation — the salvation to which we traditionally refer — that has a person avoiding God’s wrath by being found in the Book of Life.

2 Peter 3:9

“The Lord is not slow in keeping his promise, as some understand slowness. Instead he is patient with you, not wanting anyone to perish [apolesthai], but everyone to come to repentance.”

God’s in-time interests can be confounded by other interests of God, like his allowing us freedom, and his forbearing subtlety. But God’s ultimate interests will never be confounded; “All my desire I shall do.”

This verse expresses God’s forbearance, waiting until just the right time to pull the trigger on Judgment. It may be a long, long time until that happens. Who knows?

These kinds of verses merely express God’s in-time interests. Many will not have been fully-drawn at Judgment. The way is narrow, and few find it.

Others include:

John 12:32

“And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself.”

2 Corinthians 5:18

“All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ and gave us the ministry of reconciliation: that God was reconciling the world to himself in Christ, not counting people’s sins against them. And he has committed to us the message of reconciliation.”

Romans 5:18

“Consequently, just as one trespass resulted in condemnation for all people, so also one righteous act resulted in justification and life for all people.”

I assert that these verses should not be used to make a case for PUR, since they are too-easily contested and may refer to the exclusive kind of salvation (from wrath), even under PUR theology.

One of the most egregious examples is a selective citation of John 3:

John 3:17

For God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but to save the world through him.

But note the following verse:

Whoever believes in him is not condemned, but whoever does not believe stands condemned already because they have not believed in the name of God’s one and only Son.

John 3:17 tells us only that Jesus didn’t bring along with him additional condemnation above what one would already expect for sin: An equitable, wrathful recompense.

A prudent theology is self-critical. That’s why we must use discernment and care when we make our eschatological case, no matter which camp we belong to.

Q: The wages of sin is death. How do we know God isn’t “okay” with the unrighteous getting what’s coming to them?

A: We know through reason, and we know through Scripture.

Through reason, we know that he isn’t content with this because otherwise he wouldn’t do anything special — even die on a cross — to help anyone out. If his love and his wrath were equally weighted, something like a theological “Newton’s First Law” would be in effect: There would be no positive motivation to change the momentum of anyone’s deadly fate.

Through Scripture, we know that it is an ultimate or axial interest of God that a person come to repentance and redemption. He relaxes this interest only lamentably, and only when it would serve an ancillary purpose. For example, if a person deserves death, God would rather have that person repent, and he settles with deadly consequences only regrettably.

This is explained in Ezekiel 33:11:

“Say to them, ‘As surely as I live, declares the Sovereign Lord, I take no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but rather that they turn from their ways and live. Turn! Turn from your evil ways! Why will you die, people of Israel?'”

Combine this with Christ’s conquest of the grave (death’s doors are flung open) and with the universal submission and full confession (Romans 14), and we’re left with the benign, analytical conclusion that God’s love will be universally victorious by means of his wisdom and justice.

St. Gregory of Nyssa described it this way, 4th century:

“Justice and wisdom are before all these; of justice, to give to every one according to his due; of wisdom, not to pervert justice, and yet at the same time not to dissociate the benevolent aim of the love of mankind from the verdict of justice, but skilfully to combine both these requisites together, in regard to justice returning the due recompense, in regard to kindness not swerving from the aim of that love of man.”

Q: You bring up justice, but endless hell believers say that justice for sin demands an infinite penalty. How do you respond?

A: Endless hell violates the Biblical definition of God’s ultimate justice. God’s ultimate justice is this: Repaying in equity according to what a person did. That’s the definition.

Endless hell believers don’t like this definition, because it’s measured. A person who does more bad things gets a worse punishment. A person who does fewer bad things gets a lighter punishment. That’s what “according to” means.

But that’s the definition we’re given over and over and over again in Scripture:

From one of the oldest books, the Book of Job…

He repays everyone for what they have done; he brings on them what their conduct deserves. It is unthinkable that God would do wrong, that the Almighty would pervert justice. (Job 34:11-12, God’s unrebuked introducer, Elihu, speaking)

From the Gospel…

For the Son of Man is going to come in his Father’s glory with his angels, and then he will repay each person according to what they have done. (Matthew 16:27)

From Paul’s eschatology…

But because of your stubbornness and your unrepentant heart, you are storing up wrath against yourself for the day of God’s wrath, when his righteous judgment will be revealed. God ‘will repay each person according to what they have done.’ (Romans 2:5-6, against the hypocrites)

And again…

For we must all appear before the judgment seat of Christ, so that each of us may receive what is due us for the things done while in the body, whether good or bad. (2 Corinthians 5:10)

From the conclusion of Revelation…

Let the one who does wrong continue to do wrong; let the vile person continue to be vile; let the one who does right continue to do right; and let the holy person continue to be holy. Look, I am coming soon! My recompense is with me, and I will give to each person according to what they have done. (Revelation 22:11-12)

From the Psalms, in a bi-fold definition of God’s benevolence broadly…

“One thing God has spoken, two things I have heard: ‘Power belongs to you, God, and with you, Lord, is unfailing love’; and, ‘You repay everyone according to what they have done.'” (Psalm 62:11-12)

In other words, with the grave conquered, only PUR maintains the Biblical definition of God’s justice. Indeed, it doesn’t make any sense to punish infinitely for a measurable crime. This is why you so often hear endless hell believers invoke God’s “higher ways/thoughts”; it’s a hand-wave that means, “I know this doesn’t make sense, but please, just accept it.”

Thankfully, Scripture supplies us with the definition above. God’s ultimate justice is mysterious in how it’s playing-out globally (as the Book of Job explains), but its definition — equitable recompense — is not mysterious at all.

Purgatorialists “win” the argument when it comes to the Biblical definition of justice.

That’s why an extra maneuver is necessary to “adjust” the gravity of a sin to warrant unbridled suffering in return using some sort of ferried-in coefficient.

We could call this “sin algebra.”

“Sin algebra” is a perversion of justice whereby an extraneous consideration is added to the scales to force a preferred balance. Scripture has many examples of justice perversions, including bias against foreigners, indifference to widows, bribery, and incorporating the great status of a claimant.

13th century luminary St. Thomas Aquinas’s “sin algebra” looked like this:

“The magnitude of the punishment matches the magnitude of the sin. Now a sin that is against God is infinite; the higher the person against whom it is committed, the graver the sin — it is more criminal to strike a head of state than a private citizen — and God is of infinite greatness. Therefore an infinite punishment is deserved for a sin committed against Him.”

The simple rebuttal is that we mete greater punishment for injury against high human officials for consequential deterrence only. Indeed, if you ask someone to find this “sin algebra” in Scripture, they’ll have a hard time. Ask them for a passage that defines justice in this manner, and they’ll fail.

Sort of.

You see, St. Thomas Aquinas and the Scholastics didn’t actually “invent” this. It’s more proper to say that they picked some pre-chewed gum off the wall-of-rebuked-theology and started chewing it (gross, I know).

You will find this idea in Scripture, in only one general area: The rebuked diatribes of Eliphaz and Bildad, two of the “Three Stooges” of the Book of Job. Eliphaz and Bildad take this approach when Job insists that he hasn’t sinned enough to warrant his suffering.

Their logic is specifically rebuked by God’s introducer, Elihu, and they are broadly rebuked by God himself thereafter.

Job 35:4-8a

“I would like to reply to you [Job] and to your friends with you [the Three Stooges, Eliphaz, Zophar, and Bildad]. Look up at the heavens and see; gaze at the clouds so high above you. If you sin, how does that affect him? If your sins are many, what does that do to him? … Your wickedness only affects humans like yourself.”

In other words, our sins are disappointing to God, but they don’t damage him, and God’s loftiness vs. our lowliness makes them less injurious, not more.

We sinners are frustrating little creations. Pathetic, yes. In need of fixing, yes. But not “maggots” (to use Bildad’s word) that warrant whatever unbridled flaying.

See this article for more about what the Book of Job tells us about eschatology, theodicy, and God’s character.

Clarifications

Q: Is this the same thing as Catholic Purgatory?

A: No. Catholics believe in both endless hell and in a purgatorial “antechamber.” It is a spiritual state reserved for those who are saved, but where their sins warranted temporal discipline that has yet to be dished-out. Catholic Purgatory “catches” this discipline and handles it. It’s unpleasant, but everyone who goes there is heaven-bound, so there’s happiness as well. Meanwhile, those not needing Purgatory fly straight through, and some other number of souls end up in endless hell.

Q: Why become a believer? Why not just sin, sin, sin, since you’ll be reconciled eventually?

A: This relies on a false premise. To accept this argument, one must have the premise that a life of “sin, sin, sin,” is in-and-of-itself “better” than a life of sanctification and relationship with God, and thus that latter life of sanctification and relationship with God needs endless hell as a crutch or buttress in order to “win” against a life of “sin, sin, sin”; that sanctification and relationship with the Creator of the Universe, and the duty of the ministry he calls us to, is not valuable enough to make it preferred over the ‘benefits’ sinning and faithlessness.

This is a ridiculous premise. Any believer that realizes they’re holding this premise should be concerned. As the Parable of the Prodigal Son shows us, “sin, sin, sin” is the way of swine and muck. It is not praiseworthy in any way. And the humiliation, agony, and dishonor of hell remains firmly in place.

Here is a list of excellent features of coming to faith in Christ. This list doesn’t go away upon adoption of PUR theology. The idea that it does is a non sequitur, specifically a kind of “Kochab’s Error.”

Q: But why does any of that interim stuff matter, if we’re all reconciled at the end of the day?

A: That degree of “at the end of the day” is radically reductive and destroys interim meaning. There is meaning to our lives, thoughts, actions, words, love, relationships, families, struggles, blessings, and punishments beyond “what happens in the very very end.”

Q: Okay, but isn’t there less urgency, if hell is purgatorial?

A: It is less urgent, but still urgent, since a real punishment looms from a wrathful (but just!) God. It is akin to saying that you’ll serve a year for theft rather than suffer ceaselessly for it; it would be absurd to say that the deterrent force against theft is eliminated thereby.

And, of course, urgency does not entail veracity. For example, an unjust, overpunishing God would compel greater urgent response. That doesn’t mean we should believe in an unjust, overpunishing God.

For each virtue there are two bookends of vice. The virtuous view is a proper fear and respect of equitable punishment. The vice of dearth is disregard for punishment entirely. The vice of excess is worry of overpunishment. Endless hell compels the latter, which is why so many clergy have struggled with anxiety-ridden parishioners on the topic of hell.

Q: What about blasphemy against the Holy Spirit, which shall not be forgiven?

A: Blasphemy against the Holy Spirit — misattributing the work of the Spirit to something else — is indeed a sin so serious that it shall not be forgiven. All sins that are not forgiven shall receive measured, wrathful recompense. This is the simple — almost surprisingly simple — answer under PUR theology.

As it so happens, the issues around blasphemy against the Holy Spirit are much more difficult for endless hell believers to address. It doesn’t really “fit” endless hell soteriology to say that such a misstep is necessarily unforgivable.

That’s because, under most brands of endless hell theology, anything not forgiven has endless hell as consequence. It’s just obviously out-of-proportion and thus prompts horrifying anxiety in rational people. Catholic apologist Jimmy Akin writes, “Today virtually every Christian counseling manual contains a chapter on the sin to help counselors deal with patients who are terrified that they have already or might sometime commit this sin.”

And so, in rides St. Augustine on his galloping hippos to endless hell’s rescue, redefining this sin from “misattribution of the work of the Spirit to something else” — clearly the infraction that occurred in the story — to “dying in a state of stubbornness against Grace.”

Very creative! It makes no sense with the actual story — “Everyone will give account at Judgment for every empty word they have spoken,” Jesus says — but sandbags against the aforementioned anxiety issues.

Q: What about Judas? Will he be reconciled?

A: We don’t know, but I think so.

St. Gregory of Nyssa didn’t think so, since the Bible says it would have been better for him never to have been born. He reasons, “For, as to [Judas and men like him], on account of the depth of the ingrained evil, the chastisement in the way of purgation will be extended into infinity.”

Indeed, there are many varieties of PUR theology. Don’t feel bound to a specific take on it. Do your own study and exploration.

I think “better never to have been born” is better taken as an idiom. It means his station is woeful — really, really woeful.

Consider what Solomon wrote, in his existential exploration:

“Again I looked and saw all the oppression that was taking place under the sun: I saw the tears of the oppressed — and they have no comforter; power was on the side of their oppressors — and they have no comforter. And I declared that the dead, who had already died, are happier than the living, who are still alive. But better than both is the one who has never been born, who has not seen the evil that is done under the sun.”

Judas was seized with remorse (Matthew 27:3-5). That means there was some good left in him, something to be salvaged, in Judas and perhaps people like him. This perhaps extends even to monsters like Adolf Hitler, who while a charismatic villain and brilliant in many ways, was also very, very screwed-up and stupid. He will receive his just recompense. I don’t envy what awaits him.

Q: What about Satan? Will he be reconciled?

A: We don’t know, but I don’t think so.

It depends on what Satan “is.” We don’t know exactly how he “works.” Perhaps he has some good left in him that can be salvaged. Perhaps, however, he was created as enmity-in-form (the “Lucifer” backstory is an erroneous folktale, Luther and Calvin rightly observe), and as such his redemption is an instance of “Winning the Mountain Game.” If so, his fate would be annihilation or sequestration, a special exception according to his special, by-nature antagony.

Again, there are varieties of PUR theology, and many debates to be had from the PUR foundation. St. Jerome tells us that most believers — or, at least, most of his purgatorialist ilk — in his day did believe in the eventual redemption of Satan: “I know that most persons understand by the story of Nineveh and its king, the ultimate forgiveness of the devil and all rational creatures.” (Commentary on Jonah)

But for my part, I doubt it.

Addressing Other Interpretations

Q: What about the impassable chasm of Luke 16?

A: This has nothing to do with the hell of Judgment. Luke 16’s story is about a descent into Gr. Hades / Heb. Sheol, the “Grave Zone” of Hebrew folk eschatology. Hades/Sheol are emptied at Judgment per Revelation 20. Regardless of what you think happens afterward, its chasm is moot.

For more about the difference between “Hades/Sheol” and “the hell of Judgment,” see this article, which also includes a discussion of the parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man.

It’s important to point out that St. Augustine completely missed this distinction, conflating the two and allowing this blunder to infect this theology, and the theology of the church broadly thereby.

Q: What about the Jesus’s reference to the immortal worms and unquenchable fire in Mark 9?

A: This is a reference to the corpses of Isaiah; the figurative fate of God’s enemies. Christ’s thesis is that it’s better to remove stumbling-catalysts than to stumble and thereby become an enemy of God, defeated in the end.

It cannot be used in support of an endless experiential torment; these are unthinking corpses laid to waste on the field. Annihilationists can claim a “face value” victory here, but then might be challenged to explain in what “face value” sense Jesus asks us to amputate ourselves. This is figurative (not at all uncommon for Jesus). Read the chapter for yourself.

We further point to the mysterious following verse, 49: “Everyone will be salted with fire.” It looks as if this “unquenchable fire” will affect everyone to some degree or another, spurring convicted change or eventual purgation.

Q: I see the Bible talk about “endless punishment” over and over again. I see the “smoke of their torment rising forever and ever.” What gives?

A: These come from reckless, imprudent, widespread, and popular translations of the Gr. aion / aionios / aionion word family. This is the toughest sticking point. Indeed, it is the only really resilient hanger upon which the ugly sweater of endless hell hangs, and it’s baked into the vast majority of Bible translations.

Aion means age. Aionios & aionion mean “of ages” or “age-pertaining,” often with overtones of gravity or significance. More prudent translations would read, “punishment of ages” or “punishment of the age,” and “smoke of their torment rising to ages of ages.”

When we scan through both modern and ancient lexicography, we see a bunch of different views. One view is that the word family is silent on finitude/infinitude and can qualify things of any duration. Another view is that the word family adopts finitude/infinitude according to context and that which the words qualify. And, of course, some modern lexicographies under ubiquitous endless hell belief say they wholly mean “everlasting,” when that was the domain of Gr. aidios.

We see that Hesychius of Alexandria, a Hellenic lexicographer from the late 4th century, defined aion as simply, “The life of a man, the time of life,” in his “Alphabetical Collection of All Words.” Bishop Theodoret of the theological school of Antioch, early 5th century, took the view that aion adopted the meaning of that which it qualified: “An interval denoting time, sometimes infinite when spoken of God, sometimes proportioned to the duration of the creation, and sometimes to the life of man.”

But in investigating aionios specifically, the task becomes more difficult. Plato used the term occasionally but idiosyncratically. From what we can tell, our best clue on aionios specifically comes from Olympiodorus.

6th century Hellenic scholar Olympiodorus’s story is of very high interest to us. His story takes place a century into endless hell becoming dominant in the church. Olympiodorus found himself in contest with Christians who, by this time, were unanimous in treating these words as equivocal with “everlasting.” This was corrupting their interpretation of Aristotle, and Olympiodorus’s commentaries elucidate this “intrusion of theologians.”

Olympiodorus spoke of Tartarus, the Hellenic idea of the bad afterlife and analogue to the hell of Judgment, this way:

“Tartarus is a place of judgment and retribution, which contains the places of retribution … into which souls are cast according to the difference of their sins… Do not suppose that the soul is punished for endless ages (‘apeirou aionas’) in Tartarus. Very properly, the soul is not punished to gratify the revenge of the Deity, but for the sake of healing… we say that the soul is punished for a period ‘aionios,’ calling its life and assigned period in Tartarus an ‘aion.'”

He further wrote:

“When aionios is used in reference to a period which, by assumption, is infinite and unbounded, it means eternal; but when used in reference to times or things limited, the sense is limited to them.”

This isn’t pagan novelty, but an annoyed reclamation of how the Greek-speakers generally understood the term (this is why St. Gregory of Nyssa called a purgatorial hell “the Gospel accord”) against the new wave of endless hell believers misunderstanding it.

What does this mean for us? It means that every time you see the word “forever” or “everlasting” in Scripture, you may need to double-check whether the underlying word is Gr. aion / aionios / aionion. If it is, then the translation you use may be “begging the question” in service of endless hell as a “given.”

It’s important to understand that without this “question” settled in favor of endless hell, endless hell belief no longer has any Biblical case left. Only annihilationism and PUR remain with positive cases, but remain divided over how to interpret apoleia and the recognition of God’s stated preference-stacking, promises, and plans.

Q: Matthew 25:46 says, “Then they will go away to kolasin aionion [punishment of ages], but the righteous to zoen aionion [life of ages].” We know that the zoen aionion lasts forever. The parallelism shows us that the kolasin aionion must last forever, right?

A: This is an ancient, unsound argument in the “hell’s duration” debate.

Here’s some reading to help detect the unsoundness. It’s tricky, but it’s discernible:

- An Ancient, Unsound Argument in the “Hell’s Duration” Debate.

See especially the analogy to Habakkuk 3:6 in the end.

– - The Gift Game & Prudent Hermeneutics.

This thought exercise helps us see why “information from parallelism” is reckless and wrong.

Q: Does that mean that the zoen aionion is limited, too?

A: No; this would be a non sequitur. But first we need to do a quick untangling.

Both endless hell believers and purgatorial hell believers agree that the saved and unsaved receive everlasting perpetuity, that is, we will all continue onward forever. So (these two camps would agree) the zoen aionion doesn’t mean, in the strictest sense, “immortality” (like Gr. athanasia and aphtharsia).

Rather, it means life-of-ages, especially related to the Messianic Age. It represents having rushed-in to the Kingdom of God, where we can know the Father and the Son whom he sent. This direct interaction and revelation is the zoen aionion.

At Judgment, the zoen aionion (or aionios zoe) entails being found in the Biblou tes Zoes — the Book of Life.

Rather than being disowned (Matthew 10:32-33), Christ will advocate for us (Revelation 3:5). We receive a special inheritance that “can never perish, spoil, or fade… kept in heaven” (1 Peter 1:4). We eschew the “perishable crown” now in order to inherit the “imperishable crown” (1 Corinthians 9:25).

1 Corinthians 15 describes the general resurrection starting with those that belong to him. Then the end will come, and all enemies will be subdued… even death itself. “The last enemy to be destroyed is death” (1 Corinthians 15:26).

This only becomes confusing when we read the zoen aionion / aionios zoe strictly as “immortality.” Consider the rich young man in Matthew 19. He asks, “What good thing must I do to receive zoen aionion?” We imagine that he’s asking about living forever. But Jews in the Pharisaic tradition at the time already believed in a general resurrection (John 11:24, 2 Maccabees 12:38-46).

Rather, he’s talking about entering the zoen aionion: Knowing God, which (per Matthew 9:21) means righteousness now and inheriting “treasure in heaven” later. It is the “Life of the Age,” not “immortality.”

How do you get in? The commandments, which are fulfilled in love. But this rich young man needed to do one more thing. In order to receive that righteousness now and inherit that “treasure in heaven” later, he was called to give up his treasure on Earth (much like the contrast given in 1 Corinthians 9:25 and Matthew 6:19-21).

Jesus’s somber conclusion (Matthew 19:29-30):

“And everyone who has left houses or brothers or sisters or father or mother or wife or children or fields for my sake will receive a hundred times as much and will inherit zoen aionion. But many who are first will be last, and many who are last will be first.”

Only PUR preserves this “first-ness / last-ness” (vs. “first-ness / never-ness”) and maintains the original meaning of the zoen aionion / aionios zoe. Endless hell advocates are forced into cognitive dissonance, claiming that the aionios zoe literally means “everlasting life” while simultaneously proclaiming that both the saved and unsaved have endless perpetuity.

How do we know for sure that the zoen aionion / aionios zoe means “Knowing God intimately and directly through the Son”?

Three proofs:

- First, that’s how Jesus defines it in John 17:3. We don’t have to make wild guesses. The definition is sitting right here.

– - Second, that’s how it’s employed across the epistle of 1 John (the same author as recorded Jesus’s prayer above). Several verses in 1 John don’t make very much sense when we read the term as “immortality,” but make perfect sense when we read it as, “knowing God and participating in His New Covenant Kingdom, which brings with it righteousness and an inheritance.”