How “Midstream Bivalence” Leads to Reckless Philosophy

In philosophy, we all love the idea of discovering a new powerful argument, or finding a formidable refutation, or figuring out a beautiful new articulation, or validating our preconceived beliefs. We crave something confident & conclusive. And so any bug that both provides that confidence and slips past even very intelligent people is going to turn up everywhere.

Here’s one of them.

“Midstream bivalence” is a nickname for the following:

- Several premises along a syllogism enjoy large confidence but not total confidence,

and - Those premises are treated bivalently (shoehorned into either “true” or “false”),

and - When deciding whether to count those premises as “true” or “false,” we choose to “round up” that large confidence (but not total confidence) to “true.”

Those of us who have done data analysis know that these sorts of “rounding errors,” when buried within a process, are notorious for the bad and/or overconfident conclusions they can yield. But it takes some experience and/or examples to see the issue intuitively.

A syllogistic conclusion is a conjunction of all of its premises. Consider some logic within a spy story featuring 3 independent agents:

- A: Larry is on our side.

- B: Julie is on our side.

- C: Kris is on our side.

- D: Anyone on our side will fire their flare when the signal is sent.

- E: Thus, upon sending the signal, all three of Larry, Julie, and Kris will fire their flares.

This can be expressed as A&B&C&D→E.

Let’s say we’re all largely confident in each of A, B, C, and D independently. And so, we “round up” to “true” on each. This gives us T&T&T&T→T. Nice!

But… is this “okay”? It feels kind of sloppy, but it can’t be that bad, right?

Well…

… turns out it’s bad.

There are independent chances, albeit small, that each of Larry, Julie, and Kris might be double agents. Let’s say a 10% chance each.

Furthermore, there’s a chance that the agent may miss the signal for whatever reason — incapacitated, asleep, distracted, etc. Let’s say that chance is 10%… but note that it’s an independent possibility for each agent.

Now things look more like this:

- A: Larry is on our side. (P=0.9)

- B: Julie is on our side. (P=0.9)

- C: Kris is on our side. (P=0.9)

- D: If Larry is on our side, he will fire his flare when the signal is sent (P=0.9).

- E: If Julie is on our side, she will fire her flare when the signal is sent (P=0.9).

- F: If Kris is on our side, she will fire her flare when the signal is sent (P=0.9).

- G: Thus, upon sending the signal, all three of Larry, Julie, and Kris will fire their flares.

Now, if we “round up” to P=1 on each premise, then our final conclusion is P=1 as well.

But what if we refuse to “round up”? Well, any single one of the 6 premises makes the conclusion false. The way we account for the growing epistemic space of possible failure is by multiplying those probabilities together:

0.9*0.9*0.9*0.9*0.9*0.9=0.53(?!)

Oh dear.

Now what looked like a sure bet has become a coinflip.

That’s a big difference!

That’s a big… problem.

Check out the quick 5m video below for more about the scope of this problem and how it drives some of the most notorious, endless conversations in philosophy:

Bonus

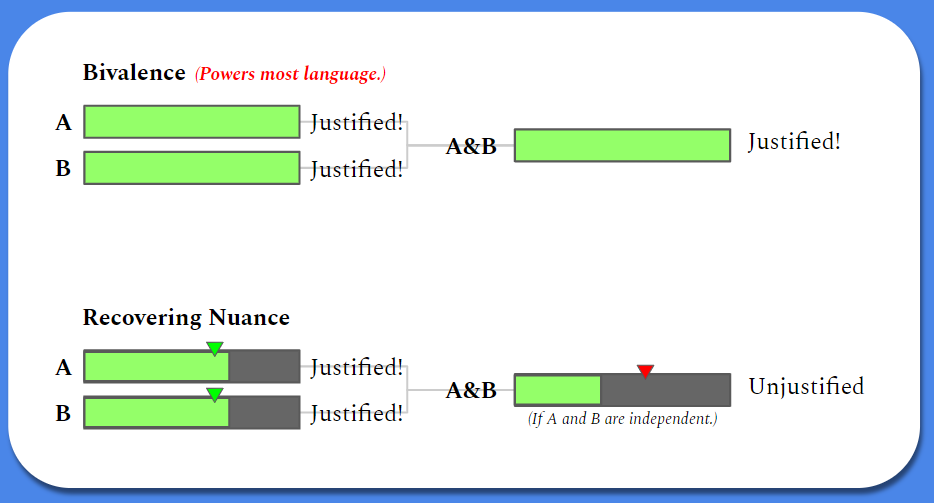

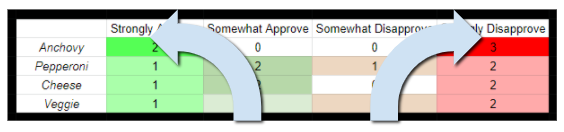

Here’s a quick diagram that quickly illustrates how, even if we define our threshold of confidence for “justification” (to “cash out” in a bivalent way), the practice of bivalent “rounding” midstream can make the difference between calling something justified or unjustified:

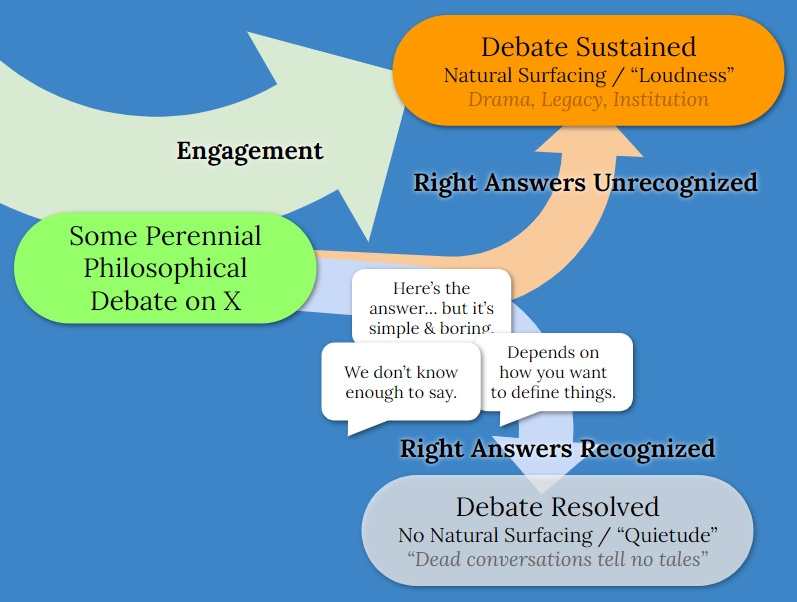

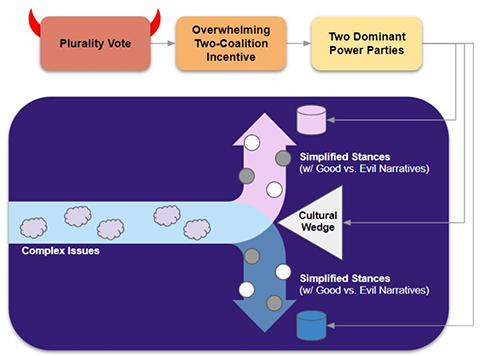

And here’s a diagram that illustrates the issue discussed in the back half of the video — selection pressures “reward” bold conclusions and obscure the fact that we already have the answers to most of the hottest (historically, and continually) philosophical debates: Usually these answers are, “It depends on how you want to define the terms,” and, “We don’t know and probably can’t know.”

These right answers are boring, they can’t be capitalized, and they end conversations. These three nails in the memetic coffin help explain philosophy’s problem with heuristic capture (in short, those whose careers & names are wholly invested in there being “more to it” cannot be trusted when they say “there’s more to it,” despite them being genuinely honest, intelligent, respectable, and endorsed by their peers — heuristics we like to lean on).

A Stupid Electoral System for Goofs

(Or, “How to Keep a Republic.”)

Election methods may seem a bit off-topic for this blog, but it couldn’t be more appropriate.

It’s a contemporary American story, and it starts with systems, flows into memetics, and finally has things to say about morality and culture, including the state of American Christianity as popularly portrayed.

Stick with me here. Each step is crucial.

Part I: Anchovy Pizza

Yes, anchovy pizza.

… Hey, I said stick with me! Your rewards will be great: You’ll soon know the 3 Clues of a Wrong Winner.

Imagine there are 5 people at a party, enough money for 1 pizza, and 4 pizza choices — cheese, pepperoni, veggie, and anchovy.

3 of the people despise anchovy pizza.

2 of the people love — absolutely adore — anchovy pizza and spurn anything else when anchovy is in play.

They want the pizza choice to represent the group. Their pizza should be like a strong republic — an expression of the “will of the people” that serves those same people and their preferences.

So what method do they use to gather group preference?

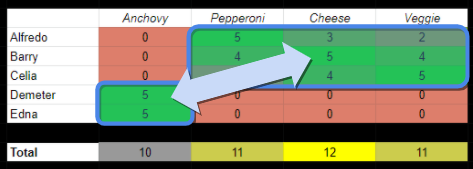

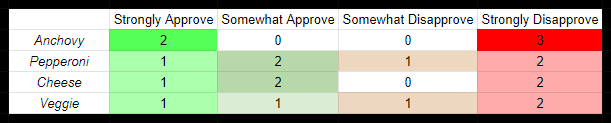

They could use Approval Vote, where each person gives “thumbs up” and “thumbs down” to each option. The pizza with the highest number of “thumbs up” wins.

Here, Cheese pizza is the winner, with 3 thumbs up.

Or, they could use Score/Range Vote, where each person gives a score to each option (here, 0 to 5). This is what we in the game development industry normally rely on for audience tests.

Again, Cheese pizza is the winner, with a score of 12. This also gives the clearest picture of where preferences fall, and in this case provides us with a powerful intuitive sense of which pizza certainly shouldn’t win (Anchovy).

Unfortunately, these 5 folks did not use the above methods.

Instead they decided to use Plurality Vote, where you mark only your very favorite option and are robbed of the ability to express anything else.

And now Anchovy pizza wins. Pretty awful, eh?

So… what happened? Well, when robbed of the ability to express anything except which choice is your very favorite, the anti-Anchovy majority got split up.

This is called, appropriately enough, “splitting the vote.”

And it’s not a joke.

In the July 1932 German federal election, Anchovy Hitler and the Nazi Party acquired a plurality of seats in the Reichstag for the first time. The use of “mark only your favorite,” combined with the number of choices involved, meant that, for all we know, the results did not express popular will in the least.

Think about it. The percentages above are not measures of popular will; they are measures of sizes of blocs of favorites. The Reichstag was apportioned according to sizes of blocs of favorites. This is stupid. A stupid system for goofs. A system simply itching to give power to the next Anchovian pied piper that comes along.

The Nazis didn’t win a majority that July — they never won a majority prior to banning the other parties — but it kicked the snowball down the slope. Emboldened by their results, they ramped up violent terrorism and increased pressure against their political rivals. A multi-way power-struggle ensued throughout the remainder of 1932, with would-be dictator Franz von Papen grasping to advance his own Machiavellian ambitions, culminating in a final, desperate re-coalition that handed the German government to the Nazis the next January. In March 1933, another election increased their seat dominance — again, leaning on the artificial advantage that Plurality Vote gives to extremists. Soon after, they passed the Enabling Act, eviscerating what separation of powers remained.

The core issue is the following stupid problem: When “mark only your favorite” is used, the sway of ideological groups is effectively divided by the number of choices in that group. Those variables should never affect one another; but here, they do. It’s as if they’re grafted together “upside-down,” since mainstream views tend to have a greater number of candidates representing them.

When this happens, the vote-splitting is given the name “spoiler effect.”

Therefore, one Clue that suggests a Wrong Winner (“Someone who won under Plurality Vote but is a bad representative of the group, i.e., would lose a head-to-head match-up vs. another candidate”) is when there’s a clear “cohort split” across ideological groups or personal loyalties (following “pied pipers”). We can call this the “Pied Piper” Clue.

But this data is sometimes hard to come by, since individual preferences can get “averaged out” in reports.

Another Clue that suggests a Wrong Winner is when the winner is uniquely polarizing or controversial, which can be measured using approval ratings.

Even though Demeter and Edna abhor the non-Anchovy options, they are unable to make the non-Anchovy options look controversial because there simply aren’t as many of them influencing the tally.

This Clue, which we’ll call the “Controversial Character” Clue, paints the following picture:

The final Clue that suggests a Wrong Winner is if, in head-to-head match-ups, or “duels,” the so-called “winner” loses most often, or even every time.

Notice what dueling does: It corrects for Plurality Vote’s devastating problem (breaking completely with more than 2 options available) by limiting the vote to 2 options only:

We’ll call that the “Duel Loser” Clue.

To recap, that’s:

- “Pied Piper” Clue. (An ideological cohort split or fringe personality.)

- “Controversial Character” Clue. (Remarkably more polarizing than others.)

- “Duel Loser” Clue. (He’s actually quite the loser, when we correct for Plurality Vote’s stupid nonsense.)

And now let’s apply these to something more contemporary: The 2016 Republican Presidential Nomination.

The Republican Primaries and Caucuses of 2016 were hotly contested between candidates Donald Trump, Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, and to a lesser extent (but still relevant) John Kasich and Ben Carson.

After March 1st’s “Super Tuesday,” 15 of the contests were over. Trump had won 337 delegates to Cruz’s 235, Rubio’s 112, Kasich’s 27, and Carson’s 8. Trump had also won 10 states vs. Cruz’s 4 and Rubio’s 1.

But every contest was either using pure Purality Vote or using a system that involved Plurality Vote at one or more stages (which is also corrupting).

Like in Germany in July 1932, the results were not necessarily measures of popular will, but of sizes of blocs of favorites.

According to the systems at play, Trump was winning after Super Tuesday. However, at this point, Trump may have been a Wrong Winner. This is a devastating possibility because Wrong Winners do not look like the losers they are. As such they gain the momentum, the loyalty, and the solidarity. (Remember when your NeverTrump uncle morphed into a Trump apologist? I certainly do.)

On March 8, one week after Super Tuesday, Langer Research Associates released a poll of Republicans and Republican-leaning voters. The researchers asked a variety of questions, and was deep enough to go “under” superficial and corrupt Plurality-style polling.

This study showed that Donald Trump was a “Controversial Character” in the sense defined before:

But, most horrifyingly, it showed that Donald Trump was a two-fold “Duel Loser”:

What a loser!

So how on Earth was he winning? Smells fishy, right?

Fishy… like an anchovy!

This is exactly the kind of ideological and/or personality-driven cohort split that makes Plurality Vote so screwed up when there are more than 2 choices on deck.

Through the Podesta e-mail leaks, we discovered that a year prior, the Clinton campaign understood that fringe candidates like Donald Trump, if legitimized, could “force all Republican candidates to lock themselves into extreme conservative positions” in order to maintain a coalition between Republican-leaning independents and the Far Right. “The variety of candidates is a positive here… we don’t want to marginalize the more extreme candidates, but make them more ‘Pied Piper’ candidates… we need to be elevating the Pied Piper candidates so that they are leaders of the pack and tell the press to [take] them seriously.”

In other words, the campaign saw that it was to their advantage to use their influence with the media to elevate Donald Trump. And when Trump became the nominee, they were pleased as punch.

But it’s important to note that Donald Trump never had a majority result until June 2016, with his big, expected win in New York. Back in March 2016, the other candidates knew what was happening, but refused to ally into an anti-Trump coalition — even as Trump averaged a 40% vote shortfall vs. the combined vote count of his strongest 2 opponents in each race.

The nonpartisan electoral reform organization FairVote, which advocates Ranked Choice Vote (another fine system), also knew what was happening: “The GOP split vote problem continues,” they wrote on March 8, 2016. “Its use of a plurality voting system may well allow a candidate to win the nomination who would be unlikely to win in a head-to-head contest with his strongest opponent.”

In other words… the Wrong Winner!

After Rubio dropped out after his disappointing result in Florida, the Cruz and Kasich campaigns called one another “spoilers.” It wasn’t until a month later that Cruz and Kasich finally set their differences aside, as their delegate shortfall grew and grew, and as Trump continued to feed off of Plurality Vote‘s toxic sewage and mutate out of control.

Cruz and Kasich came up with a “noncompete” plan so that they could stop spoiling one another, divide a few first-place wins among themselves, and push Trump into a series of second-place finishes.

Ultimately, it was the only math that could lead to a contested convention.

But it was too late.

Part II: Avoiding Anchovies

The only way to stop a Wrong Winner is to:

- Coalition in order to circumvent Plurality Vote‘s unacceptable, atrocious vote-splitting effect, and

- do so early enough so that the Wrong Winner hasn’t already captured the support and enthusiasm of the group, enchanted by his pseudo-crown, that is, the powerful — but wrong — signal that this is truly the group’s favorite.

The mainstream Republicans failed to coalition early enough to stop Donald Trump, a Wrong Winner if there ever was one, from securing the nomination. He never should have been the Republican Party candidate, and needless to say, did not represent the GOP’s platform and stated principles.

Because Plurality Vote takes a chaos-chainsaw to candidates when there are 3 or more in play, decisionmakers (whether party insiders, campaign strategists, or voters) — if they are rational decisionmakers — will do what they can to control the chaos:

- Party insiders will try to elevate somebody early, around which they can rally the masses into a united coalition.

- Campaign strategists will recommend “take-down” tactics against candidates with the biggest “my favorite!” bloc, and against candidates that share values and may be acting as direct “spoilers.”

- Voters will desperately try to stop their buddies from voting third party, since voting third party under Plurality Vote is about as helpful as eating your own ballot. Many of us intuitively sense the rational need to coalition under Plurality.

And this is why the United States is a Two Party regime.

It’s not a Two Party system; the system is Plurality Vote, which drives and sustains Two Party dominance precisely because there is no plausible, incremental way to rationally-decide our way out of it.

Put another way, to “avoid anchovies,” there is an overwhelming incentive to coalition tighter and tighter until there are only 2 choices left, because that’s the only circumstance in which Plurality Vote is fine. Failures to do this result in chaos and anti-republic results, and increase the chance of fascist and extremist cult-like personalities coming to power.

Part III: Inflame & Divide

Once there are only two viable parties left, a new overwhelming incentive emerges: Any issue that could be politicized “should” be.

With the right messaging, incoming complicated issues can be framed within a narrative in which your party is the hero and the other party is the villain — or where your party is “like us,” and the other party is “not like us.”

The leaked copy of Frank Luntz’s 2006 “The New American Lexicon” shows how neoconservatives like Luntz had been using such methods since the early 1990s to “hook” these political memeplexes into our deepest fears, hopes, and loyalties.

That messaging is “spin.” And that framing is “shoehorning.” They require dishonesty about the complexities of these issues and they require persuasive hyperbole about the “other side.”

But it’s undeniable, and irresistible. The worse the other guys look, the better you’ll do, because there are only two viable parties. Every complicated issue is “untamed land” to conquer, study, prepare, sow politicization, and reap polarization.

And the result?

Pew Research Center

Now, remember how I just used the word “irresistible?” It is mistaken to think that we can solve this problem by collectively changing our minds and deciding to come together as a country. And yet that’s how our American polarization problem is framed again and again.

If we go back one step, we notice similar “it’s our fault” framing whenever we’re stuck deciding between two candidates for President that we’re not satisfied with. “If everyone voted third party,” we hear incessantly, “we wouldn’t have to settle!”

But as we saw, Plurality Vote does not reliably produce correct winners, and the more viable candidates there are (like via third party groundswells), the more random chaos it causes.

That’s why we’re stuck in this Two Party regime.

We’re locked in it.

Part IV: Culture Power

Most of us aren’t aware that Plurality Vote gives us Wrong Winners. We assume that the system in place isn’t abysmal; we assume that the system is “good enough” that our vote “trickles up” with fidelity, and won’t betray us.

As such, we see our vote as a morally-significant expression of support.

Since we’re rationally locked-in to one of the Two Parties, we tend to rationalize those expressions of support that we give. We hitch our wagons, and our reputations, to what these “teams” are doing. It affects how we think, how we talk, how we behave, and how we socialize.

Of course, you don’t have to be a Party loyalist.

Plenty of principled libertarians can barely stomach the GOP.

Avowed leftists vote for Democrats only begrudgingly.

But the less reliable we are as Party supporters, the less the Two Parties care about us. Why grovel to purists when it’s the central terrain that’s actively contested, especially those indecisive, low-information folks who can be won-over by scaremongering and wordplay?

The Two Parties especially can’t afford to waste their energy on high-information ideological purists whose interests straddle the Party platforms. Not only are they unreliable — “disloyal” — but they can’t be won-over through clever marketing.

Who does that sound like?

That sounds to me like moderate Christians: Mainline Protestants, American Catholics, and American Orthodox.

White Evangelicals, by contrast, get lots of attention. For whatever reasons — and those reasons are myriad, really, and go back decades — white Evangelicals are reliable Republican Party loyalists.

Their strong alignment with one of the Two Parties means there’s a network of strong incentives to “boost” them, both from the Republican Party itself and from entertainment/news media profiting off of the sports-like “Civil War” narrative. So you hear from their leaders, you see them being interviewed, and when the media wants “The Christian Perspective” from “The Christian Worldview,” a white Evangelical appears on screen.

But what if they’re the “Wrong Winner” when it comes to representing Christians in the United States? They’re only 25% of Americans; Mainline Protestants, Catholics, and Orthodox combine for 35%. Notice a “Plurality Problem”?

Remember that the pseudo-crown of Wrong Winner sends a powerful — but wrong — signal that this is truly the best representative.

And, of course, this is to say nothing for the liberals and concerned conservatives whose voices within the white Evangelical cohort are tougher to hear.

For 4 years we’ve heard folks baffled that “American Christians” so openly abdicated even a pretense of moral authority in their thralldom to such a clownish, depraved political leader. The solution to the puzzle is those quotation marks at the beginning of the paragraph. The real sample of American Christians is as split as anyone else, grumbling every election cycle about the need for a third way along with the inability to muster one.

Part V: The Meaning of a Vote

Deja vu warning. (And thank you for bearing with me; you’re almost done.)

Most of us aren’t aware that Plurality Vote gives us Wrong Winners. We assume that the system in place isn’t abysmal; we assume that the system is “good enough” that our vote “trickles up” with fidelity, and won’t betray us.

As such, we see our vote as a morally-significant expression of support.

But Plurality Vote does give us Wrong Winners. The system in place is abysmal; the system is not “good enough” that our vote “trickles up” with fidelity. It can definitely betray us.

As such, we should not see our vote as a morally-significant expression of support.

Instead, it is only a helpful exertion of power, contributing to the primary mission of making sure the worst viable candidate loses.

The breakdown:

- Under fine systems, like Score/Range Vote or Ranked Choice Vote, our vote is a morally-significant expression of support.

- Under Plurality Vote, our vote is only a helpful exertion of power against the biggest threat.

Yes, the meaning of your vote just got trashed. That’s a lame meaning. It’s certainly not what we were taught.

But don’t kill the messenger.

Kill Plurality Vote.

And don’t vote like it’s gone until it’s gone.

Addendum

The politicization of ecological science is threatening the future quality of life of our children and grandchildren. This isn’t alarmism. It’s just an alarm.

We are the stewards of our families, our homes, the land we live on, the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the systems we maintain for the good of our neighbors around the planet. It’s “on us.”

And yet, there may be no plausible way to take rational action with Plurality Vote standing in the way. This is already inexplicably part of the “Culture War.” There’s only one way forward. Use your time, money, and voice to fight for electoral reform, at a local level and nationwide.

Sharing this is a good first step. Please take more steps, too.

Resources:

- The Equal Vote Coalition, advocating Score/Range Voting (S.T.A.R. method).

- FairVote, advocating Ranked Choice Voting.

- American RCV electoral reform efforts and successes thus far.

Plurality Vote won’t go away until we end it. Notice the “red” hidden within our elections. Tell others. Fight the good fight.

Potentially Bad Philosophy

Quietude might be described as as figuring out under what odd conditions it might be good to question some of our most trustworthy guides in philosophy and theology.

This is dangerous stuff, because we depend on those guides. We rely on their investment of (life)time, their investment of contentious discourse, and we take advantage of their brainpower. We stand on their shoulders. So when we choose to hop off their shoulders (or more commonly, hop onto another giant’s shoulders), we’d better have a good reason.

After we invest our trust in a person, concept (meme), or family of concepts (memeplex), it’s tough to make us leave. The speedbump we felt on the way “in” grows into a wall against going back “out.”

The feeling there is “incredulity.” As Manowar‘s 1987 heavy metal song “Carry On” claims, “100,000 riders! We can’t all be wrong!”

To keep incredulity in check, we ask, “When might even 100,000 heavy metal fans be wrong?” or more to the point, “When might dozens of brilliant philosophers be relying on fundamentally poor metaphysics?” What memetic “forces” could entrap even the otherwise trustworthy? When should we row against the current?

Viral Wildcards

We talked before about logical Wildcards. Any concept that has “vivid ambiguity” can be used, deliberately or not, to “bridge-make” (jump to conclusions that don’t really follow) and “bridge-break” (make legitimate conclusions seem like they don’t follow).

But this doesn’t just happen in isolated moments and stop there. Anything “useful” can stick and spread. This includes “Monkey’s Paw useful,” granting immediate wishes at a hidden, horrifying downstream cost.

Furthermore, that downstream cost may be “confusion, and the chatter it causes.” While we’d call this a “cost” in terms of what we consider praiseworthy and constructive, it is not a memetic cost, it is a memetic benefit.

That’s because this chatter boosts surfacing. It’s hard to hear Quiet folks.

The rhetorical utility of vivid ambiguity, combined with its natural self-surfacing, becomes a Wildcard-fueled memetic engine:

A Potential Problem

An example of the above pattern may be the philosophical concept of Aristotelian potentiality.

I’ve said before that I don’t think it’s possible to confront Wildcards directly (see the bottom-right gray box, above). All we can do is consider alternatives and try them on for size. Last time we did this with metaethics. Today it’s potentiality.

We read in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

“… Another key Aristotelian distinction [is] that between potentiality (dunamis) and actuality (entelecheia or energeia)… a dunamis in this sense is not a thing’s power to produce a change but rather its capacity to be in a different and more completed state. Aristotle thinks that potentiality so understood is indefinable, claiming that the general idea can be grasped from a consideration of cases. Actuality is to potentiality, Aristotle tells us, as ‘someone waking is to someone sleeping, as someone seeing is to a sighted person with his eyes closed, as that which has been shaped out of some matter is to the matter from which it has been shaped.’

This last illustration is particularly illuminating. Consider, for example, a piece of wood, which can be carved or shaped into a table or into a bowl. In Aristotle’s terminology, the wood has (at least) two different potentialities, since it is potentially a table and also potentially a bowl.”

(I’m not going to summarize the above so you’ll have to read it.)

This Aristotelian perspective, whereby potentiality in a sense ‘lives’ within an object, is widespread in classical Christian theology and reverberates even in modern modal analytic philosophy. But I suspect it may just be a poor (but intuitive!) way of expressing prospective imagination. I’ll show you what I mean, and why the Aristotelian sense doesn’t fit nicely with a couple examples (which in turn expose the inconsistency of the language games we play).

I can look at a quarry and imagine the potential of building a cathedral using its stone. But if we allow the test of “potential or not” to include every other requirement for cathedral assembly (including laborers to work the quarry and adequate incentives to motivate them), then it doesn’t seem so natural to say that some rock formation has such potential, in isolation. It needs help. Reductively, nothing happens unless the universe helps, including all prior states of the universe up to that point, in a cosmic help-funnel of “efficacious Grace” concluding at that final capstone. This is not simply universal reliance on some Unmoved Mover; this is, “potentiality is not real.”

In other words, in a universe empty of sculptors, but replete with rocks, no rock has potential to be sculpted. It is only when we grant the antecedent “but if there were sculptors” that its potential suddenly “is there.”

This is not real stuff. Rather, potentiality is simply a roundabout, yet shorthand way of conjoining a fact or object X with a set of antecedents, imaginary or not, which as a group are sufficient for some consequent Y. And then we utter, “X has the potential for Y.”

Aristotelian Potentiality’s Payoff

Whenever widespread language and intuitive conceptualization is imprecise in this way, we’d expect a sensible explanation for it — a rational reason why the irrational description has memetic resilience and virulence (sticky and spready).

The answer is that we’re very sub-omniscient. We don’t know very many of the facts “God knows,” so to speak. And we therefore treat the unknowns as “possible worlds,” leaning on the “holodecks of our imaginations” to narrow the focus of our prospect-seeking. This helps us avoid the anxiety of “analysis paralysis,” which is handy because, of course, the early bird gets the worm.

It should be noted that well-developed spatiotemporal faculties may be a prerequisite for using this “visual” approach to handling evaluation of contingency and consistency given uncertainty. Some studies suggest that children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder, while just as capable as others in handling counterfactuals, take different strategies to evaluate them, preferring lists of facts and their contingent relationships vs. “holodeck stories.” However, as they age they acquire skill in both.

Aristotelian Potentiality’s Discomfiture

One way to expose the irrealism of Aristotelian potential is to apply it to that which is real and closed, and find it doing conflicting things; examples where it clearly “ain’t right.”

“Sea Peoples Potential”

Consider the sentence, “The Sea Peoples who invaded Egypt in the 12th century B.C. could’ve been Aegeans.” We say “could’ve” here when we know the answer is fixed, but simply unknown. And therefore there’s a sense of “potentiality” even when it’s obvious the Sea Peoples have already come and gone, and were who-they-were.

“Fallen Coin Potential”

Another example is, “The coin could‘ve landed tails, but it landed heads.” We say “could’ve” here, and retrospectively invoke the sense of potentiality we felt 5 seconds ago, prior to the flip, when the result was unknown, and therefore probabilistic. We say this even though the result of the flip was deterministic, the fixed result of chunky kinetic forces* we humans have trouble tracking.

Put another way: “Deterministic results couldn’t be other than what they were; so why/when do we give them probabilities anyway? How on Earth do we get away with saying both ‘couldn’t’ and ‘could’ve’ about them?” These questions now have simple answers.

* (If needed, imagine the coin flip in a virtual simulated environment, to control for “quantum” or “free will” factors.)

Conclusion

I affirm the finding of a number of early 20th century philosophers that metaphysics comes down to language. It’s often buggy. These bugs sometimes foster tiny, sneaky non sequiturs that let astounding conclusions pop forth. Unless trained against these, even brilliant people are more likely to shout “Eureka!” than “Error!”

This phenomenon creates a memetic incentive to unknowingly exploit, and tendency to inherit, buggy metaphysical concepts (because we trust tradition and the brilliant, renowned people who pass it along). I suspect Aristotelian potentiality is such a thing.

Further Reading

- To explore how open language is compatible with a closed past, present, and future, read “Schrödinger’s Cup: A Closed Future of Possibilities.”

All Metaethics in Brief

It’s been over 3 years since I last posted on this blog! Where on Earth have I been?!

First, having two children is a lot harder than just one. Second, my career has become quite a bit more demanding. Third, it was hard to think of more things to say without repeating myself, and I’m happy with the amount of airtime my existing posts have been getting.

From this and direct feedback, it’s apparent that folks appreciate quiet theology. It doesn’t skyrocket YouTube hits from dramatic confrontations and rebuttals. But perhaps it accomplishes something a little better.

A while ago I made a “clip show” post that summed up my views on libertarian free will. The time has now come to make a “clip show” post on metaethics. Brazenly I assert that all metaethics can be captured in brief.

Let’s see if you agree.

- Morality is subjective in one way and objective in two ways (“SOO“). It is subjective in that it always proceeds from the interests and preferences of persons (or Persons, like God). It is objective in that there are statements about those interests that are factual (such that I could lie about them). It is also objective in that the way to optimize those interests is a strategic question with correct and incorrect answers. Any search for “ultimate objective value” is doomed to failure.

break - Ignoring or “failing to mention” the subjective component makes commands more effective. We parents learn this very quickly. It catches the listener flatfooted and often roots the imperative in what feels immovable and irresistible. In other words, there is memetic fitness in using moral language that ignores the “S” in #1. We then trick ourselves into thinking that the “SOO” framework is bad, because it fails to capture the moral language with which we’re familiar, and which proves so effective on us and others! But this is only because our familiarity has a utile error embedded in it, into which we’re inculcated from a very young age.

break - Per the 2nd “O” in #1, we tend to think consequentially. But since we’re not omniscient — in fact, we’re rather poor at anticipating all the meaningful consequences of our actions — heuristics can be helpful. While heuristics always come with certain risks, they can also give us powerful shortcuts and social cohesion. Here we distilled it into three “moral musicians”: Red (rules), green (clumsy goal-seeking), and blue (intuition). The article includes a breakdown of “minority reporting” showing that, schematically, this is indeed all a consequential system.

The above 3 observations adequately explain the existence of any metaethical position you please. In other words, take any moral theory, and you can explain it in the above terms.

This is a significant discovery if true. Right now we’re simply proposing it and trying it on for size. To do so, if you’re interested in more details about the above observations, follow the links inside to the deeper explanations. Then, put it to the test: Think of a moral theory, and see if it can be explained by the above 3 observations. A more fiery way to frame it: Try to think of a moral theory that cannot be elegantly explained by them.

Addendum for Christian readers:

These observations are also consonant with Scripture, which has a “social interest exchange” view of morality that repeatedly puts it in monetary language (covenants, debit, credit, obligation/owing, justice in merchant’s scales terms, etc.) that is alien to the purely objective moral realism of the Hellenic schools.

“Heed God” doesn’t come from him weirdly entailing some Platonic abstract. “Heed God” comes from his being Creator (so we owe him everything), Father (so he has our best interests at heart), and Judge (so he’ll eventually bring everything to account).

“Fatherhood” (so-defined) theoretically cancels out subjective impasses, like canceling out terms in math, leaving us with objective normativity in terms of our own good (remember your mom saying, “This is for your own good”?). And therefore, “at the end of the day,” nothing much changes; “during the day,” however, we enjoy a solution to the Euthyphro Dilemma that doesn’t involve (as much) special pleading.

Purgatorial Hell FAQ

Welcome to the Purgatorial Hell FAQ.

This is a tour through the issues and questions related to hell’s duration being finite rather than infinite.

It isn’t absolutely comprehensive, but I hope this is dense enough that you’ll feel that the case is made and that your questions have answers. If you have any corrections, insight, or additional questions, feel free to comment below.

Format:

Q: Question.

A: Main answer. Other details and bonus information. My own opinions on some matters.

It’s meant to be read as an article, but you can use it for reference later on.

Q: What is purgatorialism?

A: Purgatorialism is the view that hell is purgatorial (“pur” is Greek for “fire”). Hell is measured in equity according to what a person did, and is for a remedial (healing/surgical) purpose.

It is agonizing and humiliating and we should fear it, and the Good News is, in part, that we can be forgiven and avoid the wrath we’d otherwise bear.

Q: What other names does it go by?

A: It’s also called purgatorial universal reconciliation (“PUR” for short) because the end result is God’s stated master plan in Ephesians 1:8b-10:

“With all wisdom and understanding, he made known to us the mystery of his will according to his good pleasure, which he purposed in Christ, to be put into effect when the times reach their fulfillment: To bring unity to all things in heaven and on earth under Christ.”

Even though this relates specifically to the duration and nature and purpose of hell, much of Christian theology (God’s character, nature, purposes, plans, ways, and our worldview and mission methodology) is influenced by the kind of hell we believe in. The theology that proceeds from hell being finite rather than infinite is “PUR theology.”

Q: What are some related names/labels I should be aware of?

A: PUR stands in contrast to “no-punishment universalism,” the idea that the threats of God’s hellish wrath were just scare tactics and exaggerations, and — surprise! — everyone will be saved from their due punishment. This “no punishment” view — “NPUR” — cannot be reconciled with Scripture and was not believed among early Christians.

“Christian Universalism” is an attempt to differentiate universalist eschatology from the non-Christian denomination, “Unitarian Universalism.” It doesn’t go far enough, however, because a Christian Universalist may still espouse NPUR.

“Evangelical Universalism” or “EU” is sometimes used to preclude NPUR, since some folks use “Evangelical” as an idiom for a “Bible-first” heuristic. I assert this is mostly confusing, however, since “Evangelicalism” implies all sorts of unrelated things.

Q: Was it believed among early Christians?

A: Yes. It was one of the “big three” views of hell that we find in early Christian texts, even taught by orthodox Christian saints.

Those “big three” views were:

- Annihilationism. Either the unsaved are never resurrected, or there is a general resurrection and Judgment, where the saved are found in the Book of Life, and the unsaved undergo suffering, and obliterated (Arnobius, St. Ignatius of Antioch).

– - Endless hell. There is a general resurrection and Judgment, where the saved are found in the Book of Life, and the unsaved undergo suffering forever (Tertullian, Athenagoras, St. Basil the Great).

– - Purgatorial hell. There is a general resurrection and Judgment, where the saved are found in the Book of Life, and the unsaved undergo punishment measured in equity according to what a person did, and are ultimately reconciled, but through dishonor and shame, like being procured from the dross (St. Clement of Alexandria, Origen Adamantius, St. Gregory of Nyssa).

Q: Which of the “big three” views was prevalent?

A: We don’t know.

Annihilationists like to say it was annihilation. Endless hell believers like to say it was endless hell. Purgatorialists like to say it was purgatorial hell.

But we don’t really know. Complications:

- Writings from all three camps used the same Biblical language to support their view. For example, St. Irenaeus, St. Gregory of Nyssa, and St. Basil the Great would all three say that the unsaved shall suffer the kolasin aionion (the punishment-of-ages). As such, we can’t depend on such language to support any specific camp unless a writer also makes statements that further clarify their position. And many did not do this.

– - Even if all such writings were 100% unambiguous, the plurality of supporting writings does not indicate plurality of early supporters.

– - Further, plurality of existent supporting writings is an even worse indicator, since writings were, at various lamentable times, subject to selective destruction as it suited church authorities (this isn’t a conspiracy theory, but a benign fact that complicates our search).

– - And, of course, there’s the nagging fact that popularity does not entail veracity (truth/falsehood). It’s just an okay heuristic.

Q: Which of the “big three” views eventually prevailed?

A: Endless hell, of course! This happened in the 5th century, largely due to the influence of St. Augustine, a full-on Christian celebrity-theologian of his day.

St. Augustine considered it one of his missions to convince the Christian purgatorialists of endless hell, and entered into the “friendly debate” (City of God). As an endless hell believer, he’s our best “statistician” on this issue, since he admitted in Enchiridion that, in his day, there were a “great many” Christians that believed hell was purgatorial.

St. Augustine is largely responsible for the turn toward endless hell dominance in the church: He was eloquent, prolific, assertive, and creative.

Q: What are the “impasses” that divide the “big three”?

A: The “big three” cannot agree on how to interpret Gr. apoleia / apololos and Gr. aion / aionios /aionion.

The first word family is variously translated as “perishing,” “destruction,” “lost”-ness, and “cutting-off.” Annihilationists would prefer to take these literally and at face-value when possible. Those who believe in experiential hell (purgatorial hell and endless hell) say that everyone will receive perpetuity (“lingering forever”), and so these words should be taken in the sense of “lost-ness” and “cutting-off.” Purgatorialists would then say that even those lost and cut-off are salvageable, like Luke 15’s “lost (apololos) son” and “lost (apolesa) coin.”

The second word family is variously translated as “age,” “of ages,” “of the age,” “eternal,” and “everlasting.” Those who believe in an interminable doom (annihilation and endless hell) say that “eternal” and “everlasting” are good translations of these words when pertaining to the fate of the unsaved. Purgatorialists counter that such assertions are reckless and imprudent: According to the ancient lexicographers these words mean only “age-pertaining” and do not speak for the duration, but only that their duration and/or place in time is significant.

Q: So… who’s right?

A: Purgatorialists. (At least, that’s how a purgatorialist would answer!)

The Positive Case for Purgatorial Hell

Q: Enough history! Does it say in the Bible that everyone will be reconciled?

A: Yes, in Romans 11. Romans 8:18 through 11:36 is a prophetic theodicy that ends with the “upshot” of universal reconciliation.

A “theodicy” is a rationalization of some “bad thing” in terms of its being ancillary (useful and necessary as part of an optimal plan). There are experiential theodicies (specific rationalizations of specific sufferings) and abstract theodicies (showing how bad stuff could be rationalized in theory; that is, we can maintain a non-deluded hope in rationalization).

For most of us, experiential theodicy is above our paygrade. But if you’re a prophet or otherwise divinely inspired, you can be given the Grace to reveal a specific experiential theodicy.

It goes something like this:

- Admit a bad thing and lament over it.

- Postulate different ways to frame the bad thing, some of which make it more understandable.

- Appeal to God’s sovereignty over the good stuff and bad stuff.

- Postulate a reason for the bad stuff. If you’ve got guts, assert a reason for the bad stuff.

- Assert how the bad stuff is temporary.

- Assert the happy upshot with praise and thanksgiving.

- Shout God’s praises, shout the mystery of his plans, then fall flat on the floor in exhaustion.

In this case, the “bad thing” is the fact that, in Paul’s day, very few of his kin — “familiar Israel” — were recognizing Christ as the Messiah (9:2). He lamented it, even such that he’d sacrifice himself to make this bad thing not the case (9:3).

He postulates a different way to think about the bad thing; that there is a new, “spiritual” Israel of God’s elect, and so in a sense, all Israel (in this sense) has signed-on (9:6). But Paul soon returns to the discussion of regular, “familiar” Israel (9:24+, 31).

He appeals to God’s sovereignty over the good stuff and bad stuff (9:11-18), even to the degree that one might complain about God’s will being superceding over human will (9:19). But Paul holds his ground (9:20-21).

He then asserts a reason for this bad thing: The stumbling of familiar Israel is ancillary to bring in the Gentiles, who will (in turn) provoke a legitimate jealousy that will eventually bring in familiar Israel (11:11-12).

“Coming in” is contingent upon belief, but all will eventually believe. We know this because Paul says the “pleroma” will be reconciled.

Pleroma means overfull abundance, of such excess that it was used as an idiom for patched clothing. Some ultra-important theological pleromas in Scripture:

- “The Earth is the Lord’s, and the pleroma in it.” (1 Corinthians 10:26)

God is sovereign and owns absolutely everything.

– - “Whatever commands there may be are summed up in this one command: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself’ Love does no harm to a neighbor, therefore love is the pleroma of the law.” (Romans 13:9b-10)

Love completely fulfills the law under the New Covenant.

– - “For in Christ is the pleroma of the Deity, bodily.” (Colossians 2:9)

In the Trinity, Jesus Christ is full-on God, not some lesser being.

See how important pleroma is for orthodoxy?

Paul explicitly says that the elect are not the only ones with hope — the hope of reconciliation awaits even those who are not elect:

“What the people of Israel sought so earnestly they did not obtain. The elect among them did, but the others were hardened… Again I ask: Did they stumble so as to fall beyond recovery? Not at all! Rather, because of their transgression, salvation has come to the Gentiles to make Israel envious. But if their transgression means riches for the world, and their loss means riches for the Gentiles, how much greater riches will the pleroma of them bring!”

Is reconciliation for nonbelievers? Nope:

“Consider therefore the kindness and sternness of God: sternness to those who fell, but kindness to you, provided that you continue in his kindness. Otherwise, you also will be cut off (11:22).”

But is the cutting-off a sealed end? Nope:

“And if they do not persist in unbelief, they will be grafted in, for God is able to graft them in again (11:23).”

Paul wants to be clear, here. He does not want us to be “ignorant of this mystery” else we might get conceited — like Jonah or the Prodigal Son’s brother — about our “specialness” vs. the for-now hold-outs:

“I do not want you to be ignorant of this mystery, brothers and sisters, so that you may not be conceited: Israel has experienced a hardening in part until the pleroma of the Gentiles has come in, and in this way all Israel will be saved (11:25-26a).”

The ancillary purpose to God’s deliberate election and stumbling:

“Just as you who were at one time disobedient to God have now received mercy as a result of their disobedience, so they too have now become disobedient in order that they too may now receive mercy as a result of God’s mercy to you (11:30-31).”

The upshot:

“For God has bound everyone over to disobedience so that he may have mercy on them all (11:32).”

The shout:

“Oh, the depth of the riches of the wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable his judgments, and his paths beyond tracing out! Who has known the mind of the Lord? Or who has been his counselor? (11:33-34)”

Q: The pleroma stuff aside, what if some people persist in endless rebellion and refuse to confess?

A: Romans 14 says that won’t happen. Romans 14:10b-11 says, “We will all stand before God’s Judgment seat. It is written: ‘As surely as I live, says the Lord, every knee will bow before me; every tongue will fully confess to God.'”

- “Every knee will bow” is full submission. It is implausible that anyone will submit to God Himself and then pop back into rebellion like a jack-in-the-box.

– - “Every tongue will fully confess” is full confession, Gr. exomologo-. This is the attitude of those who repented and were baptized by John (“Confessing their sins, they were baptized by him in the Jordan River” Matthew 3:6) and those who heeded James’s admonishment (“Therefore, confess your sins to one another and pray for each other” James 5:16a).

This does not match with the idea of “endless rebellion” to justify endless hell or “incorrigible rebellion” to justify annihilation.

As such, some have said that Judgment at this “phase” is limited to the saved. Indeed, the context of Romans 14 is against intolerant believers. But Paul’s quoted passage from Isaiah continues: “All who have raged against him will come to him and be put to shame.”

And here it must be noted that the above idea is not found in Scripture. It was invented centuries later, “post hoc” (that is, after the “need” for such conjecture arose). So this isn’t a matter of dueling prooftexts; “endlessly-incorrigible people” lacks Scriptural warrant. Scripture instead says everyone will bend the knee, “as surely as God lives.”

The conclusion, we assert, is rock-solid: The pleroma will be reconciled, some after a cutting-off and shameful submission. The Good News is that we don’t have to be in that shamed group, and can become implements of honor, knowing God through Christ Jesus right away in the zoen aionion of the Kingdom of God.

Q: Doesn’t this, then, contradict free will?

A: No. Promises about the eventual willful submission and full confession of all people do not oppress anyone in any meaningful way. All will volunteer this submission and full confession.

The idea that such promises invalidate free will comes from a thing called the “modal scope fallacy” (in this case, one driven by an upstream composition fallacy), which very often pops out of certain ideas of free will that are ill-defined or incoherent.

Here’s a thought experiment to help explain the modal scope fallacy at play.

Let’s say there’s a 5 x 5 board containing 25 light bulbs. Each bulb can be either off, or red, or green.

Every 1 second, the whole board lights up. For each bulb, it has a 50% chance of being red and a 50% chance of being green. Then, the board shuts off again.

A bulb’s random chance to be one color or the other we can call “light bulb randomness,” or “LBR.”

Here are three board states over 3 seconds:

Seems pretty random, right? If I told you that there was LBR here, you wouldn’t complain.

But what if I said that this board showed up eventually:

Here George might say, “How could LBR still be true, here? This doesn’t look random at all; all the bulbs are the same color.”

This is an example of a modal scope fallacy. LBR is about individual bulbs. LBR doesn’t mean that the board has to look random. LBR isn’t about the board as a group. Probability dictates that it would take about a year, but we’d eventually expect all light bulbs to be the same color at least once. And if we “froze” a bulb whenever it turned green, it would take only a few seconds.

Now, this is not to say that free choices are random. This is just to show how easy it is to commit a modal scope fallacy when we’re not careful to avoid it. It’s a fallacy even some very brilliant thinkers commit.

LBR isn’t about the lightbulbs as a group, and neither is free will about humanity as a group. It’s about individual choicemaking. Free will is not at all infringed even if all individuals make the same choice eventually. And it shouldn’t matter which definition of “free will” you use.

Q: Where, though, is hell described as purgatorial?

A: 1 Corinthians 3:15-17. The context is Paul lambasting a certain group of believers who were lazy and failing to build on their initial confession — the foundation of Jesus Christ, laid down for them by Paul as “foundation-builder.”

Paul makes an eschatological threat against these believers. (We could say “so-called” believers with an failing faith; “I gave you milk, not solid food, for you were not yet ready for it. Indeed, you are still not ready. You are still worldly. … I am writing this not to shame you but to warn you as my dear children.”)

At Judgment, the bad builders are in for a bad time.

The “bad time” they’re in for:

- They’ll “suffer loss,” Gr. zemio-. “What does it profit a man to gain the whole world, but himself being lost (Gr. apolesas) or suffering loss (Gr. zemiotheis)?” That specific disownment, in the context of Luke, is the same kind threatened in Matthew 10:32-33.

– - Their “lazy servanthood” parallels that of the gold-burier of Jesus’s parable: “And throw that worthless servant outside, into the darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth” (Matthew 25:30).

In other words, this isn’t just a “tut-tutting.” This is agony and humiliation. Disownment. And the result is the Gehenna hell of Judgment (see Matthew 10:28, the cost of disownment). A deconstruction by fire, the record exposed, and the shoddy works set ablaze.

But.

The sufferer is eventually rescued. Verse 15: “But he himself shall be saved, though only as through fire.”

(It’s, of course, possible to dispute that this is about the hell of Judgment, which is the proposal on deck. But it’s not possible to dispute that this is a real threat of real loss and yet real reconciliation, which supplies a reductio ad absurdum against those who think a pre-reconciliation agony is “meaningless.”)

Q: This is confusing. The unsaved shall be saved?

A: It can be confusing because there are many senses of salvation in Scripture. This is commonly recognized by all theologians, from all three “camps.” For every kind of trouble — whether spiritual or eschatological or physical and mundane — there is a Gr. soterios “from it.”

Usually, when we say salvation, we refer to “salvation from due wrath” which also entails salvation from sin in life (through forgiveness) and from the sinful nature in life (through sanctification). And that’s usually the sense meant by “salvation” by the New Testament writers and it’s the salvation to which believers in Christ have exclusive claim.

But there is a further sense of “salvation from ultimate ‘lost-ness.'” It is a rescue from unreconciliation that everyone will eventually experience, whether or not they were saved/unsaved (in the traditional sense).

As such, these passages give us the complete Pauline eschatology. Reconciliation is contingent upon submission and confession. Everyone will eventually submit and confess. The unsaved, at Judgment, will come in shame, and will be rescued, but only as through the purging fire of wrath (which we’d much rather avoid).

St. Clement of Alexandria puts it this way, in his commentary fragment on 1 John 2:2, from the late 2nd century:

“And not only for our sins,’ — that is for those of the faithful, — is the Lord the propitiator, does he say, ‘but also for the whole world.’ He, indeed, rescues all; but some, converting them by punishments; others, however, who follow voluntarily with dignity of honor; so ‘that every knee should bow to Him, of things in heaven, and things on earth, and things under the earth.”

Q: So, Ephesians 1, Romans 11, Romans 14, 1 Corinthians 3, and 1 John 2. Any other places where an ultimate reconciliation is promised?

A: Yes. The Bible repeatedly talks of God’s in-time desire that all be saved from sin and wrath, and God’s ultimate desire that all be reconciled.

Colossians 1:15-20

“The Son is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn over all creation. For in him all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or powers or rulers or authorities; all things have been created through him and for him. He is before all things, and in him all things hold together. And he is the head of the body, the church; he is the beginning and the firstborn from among the dead, so that in everything he might have the supremacy. For God was pleased to have all his fullness [pleroma] dwell in him, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven, by making peace through his blood, shed on the cross.”

1 Timothy 2:1-6

“I urge, then, first of all, that petitions, prayers, intercession and thanksgiving be made for all people — for kings and all those in authority — that we may live peaceful and quiet lives in all godliness and holiness. This is good, and pleases God our Savior, who wants all people to be saved and to come to a knowledge of the truth. For there is one God and one mediator between God and mankind, the man Christ Jesus, who gave himself as a ransom for all people. This has now been witnessed to at the proper time.”

1 Timothy 4:10

For it is for this we labor and strive, because we have fixed our hope on the living God, who is the Savior of all men, especially of believers.

“Especially,” Gr. malista, really does mean “especially” and not “only.” See Galatians 6:10, 1 Timothy 5:8, 1 Timothy 5:17, and Titus 1:10. Paul’s letter to Timothy is consonant with Paul’s eschatology: Everyone will be saved, but believers especially so, since they’ll receive all senses of salvation, i.e., not just the ultimate reconciliation, but salvation from wrath at Judgment.

Q: Do some PUR believers cite verses that don’t strongly support PUR?

A: Yes. Some passages look at first glance to be about an ultimate reconciliation, but are actually about the earlier, exclusive salvation — the salvation to which we traditionally refer — that has a person avoiding God’s wrath by being found in the Book of Life.

2 Peter 3:9

“The Lord is not slow in keeping his promise, as some understand slowness. Instead he is patient with you, not wanting anyone to perish [apolesthai], but everyone to come to repentance.”

God’s in-time interests can be confounded by other interests of God, like his allowing us freedom, and his forbearing subtlety. But God’s ultimate interests will never be confounded; “All my desire I shall do.”

This verse expresses God’s forbearance, waiting until just the right time to pull the trigger on Judgment. It may be a long, long time until that happens. Who knows?

These kinds of verses merely express God’s in-time interests. Many will not have been fully-drawn at Judgment. The way is narrow, and few find it.

Others include:

John 12:32

“And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself.”

2 Corinthians 5:18

“All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ and gave us the ministry of reconciliation: that God was reconciling the world to himself in Christ, not counting people’s sins against them. And he has committed to us the message of reconciliation.”

Romans 5:18

“Consequently, just as one trespass resulted in condemnation for all people, so also one righteous act resulted in justification and life for all people.”

I assert that these verses should not be used to make a case for PUR, since they are too-easily contested and may refer to the exclusive kind of salvation (from wrath), even under PUR theology.

One of the most egregious examples is a selective citation of John 3:

John 3:17

For God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but to save the world through him.

But note the following verse:

Whoever believes in him is not condemned, but whoever does not believe stands condemned already because they have not believed in the name of God’s one and only Son.

John 3:17 tells us only that Jesus didn’t bring along with him additional condemnation above what one would already expect for sin: An equitable, wrathful recompense.

A prudent theology is self-critical. That’s why we must use discernment and care when we make our eschatological case, no matter which camp we belong to.

Q: The wages of sin is death. How do we know God isn’t “okay” with the unrighteous getting what’s coming to them?

A: We know through reason, and we know through Scripture.

Through reason, we know that he isn’t content with this because otherwise he wouldn’t do anything special — even die on a cross — to help anyone out. If his love and his wrath were equally weighted, something like a theological “Newton’s First Law” would be in effect: There would be no positive motivation to change the momentum of anyone’s deadly fate.

Through Scripture, we know that it is an ultimate or axial interest of God that a person come to repentance and redemption. He relaxes this interest only lamentably, and only when it would serve an ancillary purpose. For example, if a person deserves death, God would rather have that person repent, and he settles with deadly consequences only regrettably.

This is explained in Ezekiel 33:11:

“Say to them, ‘As surely as I live, declares the Sovereign Lord, I take no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but rather that they turn from their ways and live. Turn! Turn from your evil ways! Why will you die, people of Israel?'”

Combine this with Christ’s conquest of the grave (death’s doors are flung open) and with the universal submission and full confession (Romans 14), and we’re left with the benign, analytical conclusion that God’s love will be universally victorious by means of his wisdom and justice.

St. Gregory of Nyssa described it this way, 4th century:

“Justice and wisdom are before all these; of justice, to give to every one according to his due; of wisdom, not to pervert justice, and yet at the same time not to dissociate the benevolent aim of the love of mankind from the verdict of justice, but skilfully to combine both these requisites together, in regard to justice returning the due recompense, in regard to kindness not swerving from the aim of that love of man.”

Q: You bring up justice, but endless hell believers say that justice for sin demands an infinite penalty. How do you respond?

A: Endless hell violates the Biblical definition of God’s ultimate justice. God’s ultimate justice is this: Repaying in equity according to what a person did. That’s the definition.

Endless hell believers don’t like this definition, because it’s measured. A person who does more bad things gets a worse punishment. A person who does fewer bad things gets a lighter punishment. That’s what “according to” means.

But that’s the definition we’re given over and over and over again in Scripture:

From one of the oldest books, the Book of Job…

He repays everyone for what they have done; he brings on them what their conduct deserves. It is unthinkable that God would do wrong, that the Almighty would pervert justice. (Job 34:11-12, God’s unrebuked introducer, Elihu, speaking)

From the Gospel…

For the Son of Man is going to come in his Father’s glory with his angels, and then he will repay each person according to what they have done. (Matthew 16:27)

From Paul’s eschatology…

But because of your stubbornness and your unrepentant heart, you are storing up wrath against yourself for the day of God’s wrath, when his righteous judgment will be revealed. God ‘will repay each person according to what they have done.’ (Romans 2:5-6, against the hypocrites)

And again…

For we must all appear before the judgment seat of Christ, so that each of us may receive what is due us for the things done while in the body, whether good or bad. (2 Corinthians 5:10)

From the conclusion of Revelation…

Let the one who does wrong continue to do wrong; let the vile person continue to be vile; let the one who does right continue to do right; and let the holy person continue to be holy. Look, I am coming soon! My recompense is with me, and I will give to each person according to what they have done. (Revelation 22:11-12)

From the Psalms, in a bi-fold definition of God’s benevolence broadly…

“One thing God has spoken, two things I have heard: ‘Power belongs to you, God, and with you, Lord, is unfailing love’; and, ‘You repay everyone according to what they have done.'” (Psalm 62:11-12)

In other words, with the grave conquered, only PUR maintains the Biblical definition of God’s justice. Indeed, it doesn’t make any sense to punish infinitely for a measurable crime. This is why you so often hear endless hell believers invoke God’s “higher ways/thoughts”; it’s a hand-wave that means, “I know this doesn’t make sense, but please, just accept it.”

Thankfully, Scripture supplies us with the definition above. God’s ultimate justice is mysterious in how it’s playing-out globally (as the Book of Job explains), but its definition — equitable recompense — is not mysterious at all.

Purgatorialists “win” the argument when it comes to the Biblical definition of justice.

That’s why an extra maneuver is necessary to “adjust” the gravity of a sin to warrant unbridled suffering in return using some sort of ferried-in coefficient.

We could call this “sin algebra.”

“Sin algebra” is a perversion of justice whereby an extraneous consideration is added to the scales to force a preferred balance. Scripture has many examples of justice perversions, including bias against foreigners, indifference to widows, bribery, and incorporating the great status of a claimant.

13th century luminary St. Thomas Aquinas’s “sin algebra” looked like this:

“The magnitude of the punishment matches the magnitude of the sin. Now a sin that is against God is infinite; the higher the person against whom it is committed, the graver the sin — it is more criminal to strike a head of state than a private citizen — and God is of infinite greatness. Therefore an infinite punishment is deserved for a sin committed against Him.”

The simple rebuttal is that we mete greater punishment for injury against high human officials for consequential deterrence only. Indeed, if you ask someone to find this “sin algebra” in Scripture, they’ll have a hard time. Ask them for a passage that defines justice in this manner, and they’ll fail.

Sort of.

You see, St. Thomas Aquinas and the Scholastics didn’t actually “invent” this. It’s more proper to say that they picked some pre-chewed gum off the wall-of-rebuked-theology and started chewing it (gross, I know).

You will find this idea in Scripture, in only one general area: The rebuked diatribes of Eliphaz and Bildad, two of the “Three Stooges” of the Book of Job. Eliphaz and Bildad take this approach when Job insists that he hasn’t sinned enough to warrant his suffering.

Their logic is specifically rebuked by God’s introducer, Elihu, and they are broadly rebuked by God himself thereafter.

Job 35:4-8a

“I would like to reply to you [Job] and to your friends with you [the Three Stooges, Eliphaz, Zophar, and Bildad]. Look up at the heavens and see; gaze at the clouds so high above you. If you sin, how does that affect him? If your sins are many, what does that do to him? … Your wickedness only affects humans like yourself.”

In other words, our sins are disappointing to God, but they don’t damage him, and God’s loftiness vs. our lowliness makes them less injurious, not more.

We sinners are frustrating little creations. Pathetic, yes. In need of fixing, yes. But not “maggots” (to use Bildad’s word) that warrant whatever unbridled flaying.

See this article for more about what the Book of Job tells us about eschatology, theodicy, and God’s character.

Clarifications

Q: Is this the same thing as Catholic Purgatory?

A: No. Catholics believe in both endless hell and in a purgatorial “antechamber.” It is a spiritual state reserved for those who are saved, but where their sins warranted temporal discipline that has yet to be dished-out. Catholic Purgatory “catches” this discipline and handles it. It’s unpleasant, but everyone who goes there is heaven-bound, so there’s happiness as well. Meanwhile, those not needing Purgatory fly straight through, and some other number of souls end up in endless hell.

Q: Why become a believer? Why not just sin, sin, sin, since you’ll be reconciled eventually?

A: This relies on a false premise. To accept this argument, one must have the premise that a life of “sin, sin, sin,” is in-and-of-itself “better” than a life of sanctification and relationship with God, and thus that latter life of sanctification and relationship with God needs endless hell as a crutch or buttress in order to “win” against a life of “sin, sin, sin”; that sanctification and relationship with the Creator of the Universe, and the duty of the ministry he calls us to, is not valuable enough to make it preferred over the ‘benefits’ sinning and faithlessness.

This is a ridiculous premise. Any believer that realizes they’re holding this premise should be concerned. As the Parable of the Prodigal Son shows us, “sin, sin, sin” is the way of swine and muck. It is not praiseworthy in any way. And the humiliation, agony, and dishonor of hell remains firmly in place.

Here is a list of excellent features of coming to faith in Christ. This list doesn’t go away upon adoption of PUR theology. The idea that it does is a non sequitur, specifically a kind of “Kochab’s Error.”

Q: But why does any of that interim stuff matter, if we’re all reconciled at the end of the day?

A: That degree of “at the end of the day” is radically reductive and destroys interim meaning. There is meaning to our lives, thoughts, actions, words, love, relationships, families, struggles, blessings, and punishments beyond “what happens in the very very end.”

Q: Okay, but isn’t there less urgency, if hell is purgatorial?

A: It is less urgent, but still urgent, since a real punishment looms from a wrathful (but just!) God. It is akin to saying that you’ll serve a year for theft rather than suffer ceaselessly for it; it would be absurd to say that the deterrent force against theft is eliminated thereby.

And, of course, urgency does not entail veracity. For example, an unjust, overpunishing God would compel greater urgent response. That doesn’t mean we should believe in an unjust, overpunishing God.

For each virtue there are two bookends of vice. The virtuous view is a proper fear and respect of equitable punishment. The vice of dearth is disregard for punishment entirely. The vice of excess is worry of overpunishment. Endless hell compels the latter, which is why so many clergy have struggled with anxiety-ridden parishioners on the topic of hell.

Q: What about blasphemy against the Holy Spirit, which shall not be forgiven?

A: Blasphemy against the Holy Spirit — misattributing the work of the Spirit to something else — is indeed a sin so serious that it shall not be forgiven. All sins that are not forgiven shall receive measured, wrathful recompense. This is the simple — almost surprisingly simple — answer under PUR theology.

As it so happens, the issues around blasphemy against the Holy Spirit are much more difficult for endless hell believers to address. It doesn’t really “fit” endless hell soteriology to say that such a misstep is necessarily unforgivable.

That’s because, under most brands of endless hell theology, anything not forgiven has endless hell as consequence. It’s just obviously out-of-proportion and thus prompts horrifying anxiety in rational people. Catholic apologist Jimmy Akin writes, “Today virtually every Christian counseling manual contains a chapter on the sin to help counselors deal with patients who are terrified that they have already or might sometime commit this sin.”

And so, in rides St. Augustine on his galloping hippos to endless hell’s rescue, redefining this sin from “misattribution of the work of the Spirit to something else” — clearly the infraction that occurred in the story — to “dying in a state of stubbornness against Grace.”

Very creative! It makes no sense with the actual story — “Everyone will give account at Judgment for every empty word they have spoken,” Jesus says — but sandbags against the aforementioned anxiety issues.

Q: What about Judas? Will he be reconciled?

A: We don’t know, but I think so.

St. Gregory of Nyssa didn’t think so, since the Bible says it would have been better for him never to have been born. He reasons, “For, as to [Judas and men like him], on account of the depth of the ingrained evil, the chastisement in the way of purgation will be extended into infinity.”

Indeed, there are many varieties of PUR theology. Don’t feel bound to a specific take on it. Do your own study and exploration.

I think “better never to have been born” is better taken as an idiom. It means his station is woeful — really, really woeful.

Consider what Solomon wrote, in his existential exploration:

“Again I looked and saw all the oppression that was taking place under the sun: I saw the tears of the oppressed — and they have no comforter; power was on the side of their oppressors — and they have no comforter. And I declared that the dead, who had already died, are happier than the living, who are still alive. But better than both is the one who has never been born, who has not seen the evil that is done under the sun.”

Judas was seized with remorse (Matthew 27:3-5). That means there was some good left in him, something to be salvaged, in Judas and perhaps people like him. This perhaps extends even to monsters like Adolf Hitler, who while a charismatic villain and brilliant in many ways, was also very, very screwed-up and stupid. He will receive his just recompense. I don’t envy what awaits him.

Q: What about Satan? Will he be reconciled?

A: We don’t know, but I don’t think so.

It depends on what Satan “is.” We don’t know exactly how he “works.” Perhaps he has some good left in him that can be salvaged. Perhaps, however, he was created as enmity-in-form (the “Lucifer” backstory is an erroneous folktale, Luther and Calvin rightly observe), and as such his redemption is an instance of “Winning the Mountain Game.” If so, his fate would be annihilation or sequestration, a special exception according to his special, by-nature antagony.

Again, there are varieties of PUR theology, and many debates to be had from the PUR foundation. St. Jerome tells us that most believers — or, at least, most of his purgatorialist ilk — in his day did believe in the eventual redemption of Satan: “I know that most persons understand by the story of Nineveh and its king, the ultimate forgiveness of the devil and all rational creatures.” (Commentary on Jonah)

But for my part, I doubt it.

Addressing Other Interpretations

Q: What about the impassable chasm of Luke 16?

A: This has nothing to do with the hell of Judgment. Luke 16’s story is about a descent into Gr. Hades / Heb. Sheol, the “Grave Zone” of Hebrew folk eschatology. Hades/Sheol are emptied at Judgment per Revelation 20. Regardless of what you think happens afterward, its chasm is moot.

For more about the difference between “Hades/Sheol” and “the hell of Judgment,” see this article, which also includes a discussion of the parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man.

It’s important to point out that St. Augustine completely missed this distinction, conflating the two and allowing this blunder to infect this theology, and the theology of the church broadly thereby.

Q: What about the Jesus’s reference to the immortal worms and unquenchable fire in Mark 9?

A: This is a reference to the corpses of Isaiah; the figurative fate of God’s enemies. Christ’s thesis is that it’s better to remove stumbling-catalysts than to stumble and thereby become an enemy of God, defeated in the end.

It cannot be used in support of an endless experiential torment; these are unthinking corpses laid to waste on the field. Annihilationists can claim a “face value” victory here, but then might be challenged to explain in what “face value” sense Jesus asks us to amputate ourselves. This is figurative (not at all uncommon for Jesus). Read the chapter for yourself.

We further point to the mysterious following verse, 49: “Everyone will be salted with fire.” It looks as if this “unquenchable fire” will affect everyone to some degree or another, spurring convicted change or eventual purgation.

Q: I see the Bible talk about “endless punishment” over and over again. I see the “smoke of their torment rising forever and ever.” What gives?

A: These come from reckless, imprudent, widespread, and popular translations of the Gr. aion / aionios / aionion word family. This is the toughest sticking point. Indeed, it is the only really resilient hanger upon which the ugly sweater of endless hell hangs, and it’s baked into the vast majority of Bible translations.

Aion means age. Aionios & aionion mean “of ages” or “age-pertaining,” often with overtones of gravity or significance. More prudent translations would read, “punishment of ages” or “punishment of the age,” and “smoke of their torment rising to ages of ages.”