Thorny Moral Chestnuts, Pt. 2

Catchy quotes and sayings — “chestnuts” — can undergo slight mutations over time.

Sometimes, those chestnuts are proverbs or rules. And sometimes, those gradual mutations can modify those proverbs or rules so much that their original wisdom is completely destroyed, converted into non-wisdom.

Last time in this 2-part series, we talked about “The Ends Can’t Justify the Means.” Today, we’ll talk about “Ignorance is No Excuse.” Both of these are false chestnuts.

“Ignorance is No Excuse”

Let’s say you’re a manager who delegates many of your responsibilities to your subordinates.

One day, one of your subordinates mails a package without including a special serial number, and it causes problems for your team. You call him into your office.

“You’re in trouble,” you say. “You mailed a package off to finance without including the sorting number.”

“But I had no idea I was supposed to do that!” he replies.

“Ignorance is no excuse,” you say.

The thing is, it was your responsibility to train him, a week ago, in applying proper serial numbers on special packages. You know that you failed to do this; you cut the training short to pick up your dog and didn’t get to the part about numbering packages. You knew this would leave a gap in his ability to make right decisions according to your company’s processes, and yet you did it anyway, and didn’t bother to fill him in later.

The reason I transferred the responsibility for this mistake to you is because it most obviously alleviates the subordinate’s responsibility. Clearly, ignorance was a perfectly valid excuse.

How can you act upon what you did not know, and couldn’t have known?

When Ignorance is Blameworthy

Here are some alternative versions of the above thought experiment.

- You (the manager) stayed for the whole training, but the subordinate left early, and never followed-up to get the information he missed.

– - The training hasn’t happened yet, but it was expected of the subordinate to ask a superior or experienced coworker to make sure that new-to-him tasks are done properly.

In these cases, the subordinate’s ignorance was catalyzed by his own blameworthy behavior — here, negligent behavior.

“Invincible Ignorance”

Ignorance that was not catalyzed by blameworthy behavior is called “invincible ignorance.” Invincible ignorance is a legitimate excuse.

I myself am not a Catholic, but the Catechism of the Catholic Church correctly identifies this brand of ignorance (1790-1791, 1793a):

A human being must always obey the certain judgment of his conscience. If he were deliberately to act against it, he would condemn himself. Yet it can happen that moral conscience remains in ignorance and makes erroneous judgments about acts to be performed or already committed.

This ignorance can often be imputed to personal responsibility. This is the case when a man “takes little trouble to find out what is true and good, or when conscience is by degrees almost blinded through the habit of committing sin.” In such cases, the person is culpable for the evil he commits.

…

If — on the contrary — the ignorance is invincible, or the moral subject is not responsible for his erroneous judgment, the evil committed by the person cannot be imputed to him.

When Ignorance Cannot be Respected

Even though invincible ignorance is a legitimate excuse, there’s no way for one human to know for certain that another’s ignorance is invincible.

Humans lie all the time, and will (if given a cultivating environment) pretend that their blameworthy (usually by way of negligence) ignorance is invincible.

We will, in fact, lie to ourselves to alleviate guilt of this kind. “I couldn’t have known,” is a common self-encouraging mantra, when we often could have known, if only we had practiced some due exploratory diligence.

(The trick, here, is not to “overcorrect” into paranoia or worry — that is, excessive and deleterious bet-hedging and consciously-made anxiety. Diligence is a “too cold,” “too hot,” “just right,” Goldilocks issue, like with many virtues.)

Humans Can’t Verify Invincibility… but God Can

Of course, verifying invincibility isn’t a problem for an omniscient God.

This is why the judgment to which we Christians look forward judges the secret thoughts of everyone. A person’s thoughts will at times accuse them, but at other times excuse them.

Romans 2:15-16

They show that the work of the law is written on their hearts, while their conscience also bears witness, and their conflicting thoughts accuse or even excuse them on that day when, according to my gospel, God judges the secrets of men by Christ Jesus.

… But, Again, Humans Can’t

Many practical human-to-human systems will have “ignorance is no excuse” as an official position because of the impracticality of verifying invincibility.

This position, though not how morality “works,” is a decent practical rule to account for the failings of human weakness (that of one party to lie, and that of the other party to be unable to verify).

The previous article in this series, if you remember, ended similarly. And this gives us a cool pattern in the abstract against which to evaluate those funny moral chestnuts. It tells us that just because something is a classic chestnut, and is a popular rule, and is a useful rule very often, doesn’t mean it should be considered fundamental when we’re talking meta-ethics — that is, how morality “works” underneath.

Thorny Moral Chestnuts, Pt. 1

Catchy quotes and sayings — “chestnuts” — can undergo slight mutations over time.

Sometimes, those chestnuts are proverbs or rules. And sometimes, those gradual mutations can modify those proverbs or rules so much that their original wisdom is completely destroyed, converted into non-wisdom.

Today, we’ll talk about “The Ends Can’t Justify the Means.” In the next post, we’ll talk about “Ignorance is No Excuse.” Both of these are false chestnuts.

“The Ends Can’t Justify the Means”

I’m sure you’ve heard this one a billion times.

It’s usually uttered by the hero of a story, against some villain who’s decided to bring about some praiseworthy conclusion by means of a horrific plan.

“But I’ll create a better world!” cries the villain, Viktor.

“No,” responds the hero, Herbert. “The ends can’t justify the means.”

We cheer the Herbert at this point, right?

Okay. Now let’s take these characters and transplant them into a different situation.

Viktor and Herbert are shop owners in Nazi Germany. For months, they’ve been harboring a Jewish family in a secret attic above their shop. This morning, they’ve heard that Nazi investigators will be going shop to shop and asking for information about harbored Jews in the area.

“We should lie to the investigators,” says Viktor. “A little dishonesty will bring about a greater good by saving lives.”

“No,” responds the “hero,” Hubert. “The ends can’t justify the means.”

Notice how in both cases, Viktor wants to do something considered morally wrong in order to bring about a greater good. But in the latter situation, we can all clearly see that it is no longer Viktor who is the villain — rather, it is Hubert who we all rebuke as morally askew.

We’re quite practiced at cheering duty-bound heroes and chastising “good ends / ill means” supervillains. What we forget is that there are plenty of “good ends / ill means” heroes as well, from Oskar Schindler to Rahab, who we (alongside James) recognize as righteous for heroism that required deception.

The Better Chestnut

The answer to the puzzle is that “The ends can justify ill means.”

The question is, when?

Well, ends are more likely to justify ill means when:

- The ends are really, really good…

– - … and you’re really, really sure that they’ll come about.

– - The ill means aren’t that bad…

– - … and you’re really, really sure that there won’t be horrible unintended consequences, neither for those in your local area, nor for the world in general, and neither for things right now, nor for things down the road.

– - There aren’t safer, more praiseworthy ways to seek those good ends.

Similarly, ends are less likely to justify ill means when:

- The ends are good, but not that great.

– - You’re not sure they’ll come about.

– - The ill means are pretty bad.

– - You aren’t sure that there won’t be a bunch of horrible unintended consequences.

– - There are safer, more praiseworthy ways to seek those good ends.

Decisionmaking is Complicated

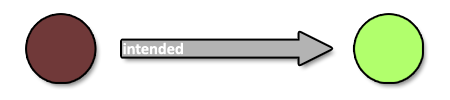

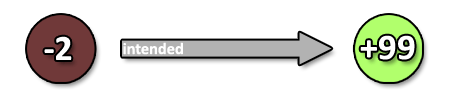

Consider the following diagram, where the ill dark-red “bad” circle is committed, while intended to make the green “good” circle come about.

Wouldn’t it be nice if it were that simple? We could say, “You can’t use bad things to make good things happen.”

In reality, those “circles” need moral weight/gravity/intensity assigned to them according to what we value.

Suddenly, that seems okay. Once we account for the moral weights, a tiny moral ill can indeed be acceptable in service of a huge moral payoff.

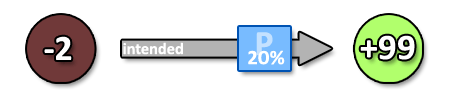

But it still isn’t that simple! We need to account for the likelihood of that good consequence coming about!

If there’s only a 20%, or one-fifth, chance of that big payoff happening, it might still be a good investment, but it’s “worth less” as a prospect. In decision theory, we call that “net worth” our “expected value” or “EV.”

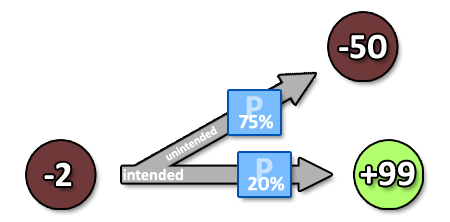

But it still isn’t that simple! We haven’t accounted for any of the consequences that are foreseeable but unintended!

Ew, gross! This decision is looking pretty ghastly now, isn’t it?

But…

… wait for it…

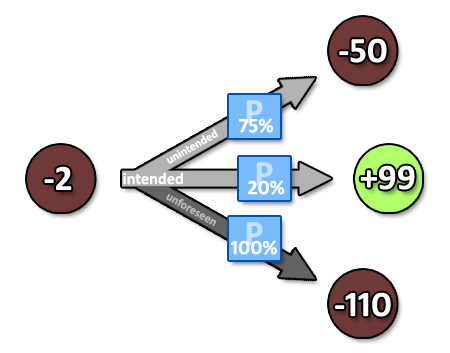

… it still isn’t that simple! That’s because there are all sorts of unforeseen consequences lurking in the shadows of human unknowability.

It turns out that we, as humans, are so bad at considering the unintended and unforeseen consequences — often when a bee-line prospect looks very tantalizing — that “blind rule-following” has a certain consequential strength or fitness. This is especially the case when, in the shadows of human unknowability, habitual ill behavior can translate into numerous personal erosions of character and will.

And that’s why “The ends can’t justify the means,” is a decent “rule” for folks who can’t handle the complications of decision theory, or who think themselves wiser and/or more knowledgeable than they really are — which is almost everybody.

But it’s not really true.

That’s what makes it thorny.

And so when we’re engaged in lofty discourse about how morality “works,” we need to be careful not to treat that thorny chestnut as fundamental or sacrosanct.

For more about how deontology (“morality is about rules”) and consequentialism (“morality is about consequences”) “converge” on the practicalities of human weakness, take a gander at the Angelic Ladder.

Correlation & Causation Pt. 2: Undead Philosophy

This is the second in a two-part series on correlation and causation, and how conflating the two can dramatically distort our perceptions and thinking.

The first part was about the exploitation by media, and the second part (below) is about the related philosophical and theological “bugs” that we must work to root-out.

Commission & Omission

Jimmy Fallon’s “Your Company’s Computer Guy,” about to recommend omitting action.

You’ve noticed that when confronted with a situation in which you must either commit action or omit action, you often take the omissive route due to a lack of information.

Acting recklessly beyond what is known can create all sorts of problems, which you know.

As a result, omissive action becomes generally correlated with “more correct” action.

But does this make omission less morally intense than commission? Is it always slightly more grevious, for example, to kill by commission than by omission?

No.

But it can feel that way due to those correlative “lessons.”

Retribution & Remediation

Corporal punishment from the movie, “Catching Fire.”

You’ve noticed that when faced with the bad decision of someone over whom you have authority, you want to react in a way that teaches that person a lesson and corrects the problem, now and for the future.

This is the remedial prospect of assigning judgment.

But you’ve also noticed that, often, the response is something punitive — frequently, Pavlovian behavior modification that requires only that the person be repaid in proportion to how much you were wronged.

As a result, justice becomes generally correlated with “retributory” action.

But does this mean that this is the “point” of justice? Is the prospective “goal” merely to repay?

No.

But it can feel that way due to those correlative “lessons.”

Assigning Responsibility

Gaius Baltar from “Battlestar Galactica”: Very blameworthy.

You’ve noticed that bad results can often be attributed to a single person making a single bad decision.

Usually, we’re all working as hard as we can for productive results, and when that goal is undermined, it’s usually because someone screwed up. If the cofactor was something mindless — like a broken pipe for which nobody has responsibility — then we often say, “Nobody is responsible.”

Thus, finding responsibility becomes generally correlated with finding a single, blameworthy decisionmaker.

But does this mean that this is how responsibility “works”? Is there always a single person solely responsible? And is it useful to limit responsible cofactors exclusively to decisionmakers? And is responsibility always about blameworthiness, never about creditworthiness?

The answer to all three is, “No.”

But it can feel like “Yes” due to those correlative “lessons.”

“Finding” Value

An invaluable gold statue of Michael Jackson.

You’ve noticed that when you look at an object of value, you think of the value “living inside” that object.

You also value things without consciously valuing them; you value food not because your rational mind is convinced of its utility, but because without food you feel hunger. That feeling is out of your control, and so it further feels like the food “contains” value.

You’ve also noticed that an object “becomes” more valuable the more work it would take to acquire or reacquire, which is not something over which you have arbitrary control.

Finally, you’ve been taught that certain things are valuable — even those things, which, if you hadn’t been taught as such, you wouldn’t value.

Thus, this constant bombardment of correlative lessons can make you feel like an object can have “intrinsic value.”

But can it, really? Would gold be valuable if there were no valuing things — that is, minds with interests — to respect it? Is value purely objective?

No.

But it can feel that way due to those correlative “lessons.”

Objective Taste

A veggie pizza from Maurizio’s.

We all agree that taste is a matter of taste. Some people are going to prefer Armanno’s Pizza on 12th and some people are going to prefer Maurizio’s Pizza on Washington.

You’ve just been hired, however, to head up local marketing for Maurizio’s. What do you do, given that taste is a matter of taste?

You could run a blind taste-test in service of finding the “aggregate taste,” such that you could boast, “Most people prefer Maurizio’s!”

Unfortunately, the results indicate that most people, in fact, prefer Armanno’s.

Uh oh.

How about this.

You put together a campaign that proclaims Maurizio’s is just better. It just “tastes better.”

It’ll be true for some people, right?

And by wrapping it in objective language, you’ve divorced it from fickle personal preferences and given it the mystique of objectivity. Its superiority has been enshrined on a pedestal that no filthy human hands have touched.

If you weren’t the marketer, someone else would be. And they’d eventually start playing around with objective language. That’s because there’s selective memetic momentum toward enshrining things preference-based as objective, preference-less facts.

Pretty sleazy, right?

But, what if the success of Maurizio’s had some huge, higher-order payoff for everyone? What if that connection was hard to show, or hard to articulate, but nonetheless 100% true? What if, in the here and now, it’s absolutely vital for society that folks be convinced to go against their personal impulsive pizza tastes and gravitate toward Maurizio’s?

Suddenly, wrapping the marketing of Maurizio’s pizza within incomplete, “objective” language, however sloppy and technically erroneous, starts to have utilitarian merit.

The language “bug” becomes useful.

But does this mean that it isn’t a bug? Does this selective momentum suggest that these things really are a matter of purely objective worth and purely objective “rightness”?

No.

But it can feel that way due to those correlative “lessons.”

Correlative Bugs

Each of these examples have been of myths, driving persistent philosophical questions, from ancient debates to contemporary contemplation.

Is commission more morally intense than omission? No. Omission is just more often correct, because it usually is less reckless (but is sometimes more negligent).

An exciting philosophical debate is resolved with boring nuance.

Is justice about pure retribution? No. Justice is about fixing a person or that which he represents in the abstract, but retribution is a very common, intuitive, and historically effective way of employing such fix attempts (even if the “fix” is “repair that which a murderer represents by locking him away forever”).

An exciting philosophical debate is resolved with boring nuance.

Is assigning responsibility about finding a single blameworthy decisionmaker? No. Assigning responsibility is about finding all causal cofactors in service of what needs to be fixed or encouraged. This just, very often, points to a single person’s behavior in need of repair.

An exciting philosophical debate is resolved with boring nuance.

Is there “intrinsic value”? No. Value is imputed by evaluators with interests. But there are all sorts of complications that make value seem, conceptually, “within object.”

An exciting philosophical debate is resolved with boring nuance.

Are there “objective interests”? No. “Subjective-as-objective” language errors are just very often useful for behavior modification, and behavior modification has been historically effective — perhaps even necessary — for social stability.

An exciting philosophical debate is resolved with boring nuance.

But the Undead are Entertaining

There’s a natural selective bias toward things that are exciting. It’s more fun to chatter than to sit in silence. Controversy is more entertaining than complacency. Story arcs sell better than story flatlines.

Remember that popular philosophy, just like anything else with the “popular” qualifier, is much more a product of memetics than of coherence or truth.

More reading:

- For a discussion of how memetics can select for the popularity of garbage, see “Memetics Pt. 2: The Four Brothers (and Their Business Booths).”

– - For more about the psychology of omission versus commission, conveyed through a personal anecdote, read “Bibliopsychology: Why the Servant Did Nothing.”

– - For a rebuttal of another bad correlative lesson — that morality is primarily about “rules” — read “The Angelic Ladder.”

– - To review the Bible’s lesson that meaning is non-objective, see “Ecclesiastes and Non-Objective Meaning.”

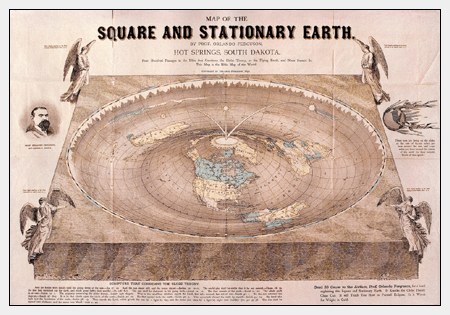

Memetics Pt. 4: Short Towers + Secret Gnosis

In the first two videos on memetics (see schedule below), we talked about how truth — and other things we like — may not be decisive when it comes to the “spreadiness” and “stickiness” of certain ideas. In other words, “goodness” does not necessarily yield “fitness.”

In the third video, we talked about how some of the neuropsychological patterns that drive our decisionmaking can prompt and prevent virulence and resilience (“spreadiness” and “stickiness”). In that video, we focused primarily on loss aversion.

In this video, we’re going to talk about another such pattern, called secret gnosis stimulation.

We’ll find out why having and enjoying “hidden knowledge” can make you feel privileged, validated, and “rooted” to your local “tower,” even if it’s not tallest. This “hidden knowledge” often takes the form of esoteric or counterintuitive claims that can be convincing when internally consistent, and/or without a competitor recognized as viable.

We’ll also discuss several specific case examples of groups of people who are rooted to false conspiracy theories. Controversial!

Secret gnosis stimulation is very effective here, too. … It gets you locked into conspiracy theories when the body of [apparent evidence for the conspiracy] is dwarfed by reality.

Schedule

- Memetics Pt. 1: Introduction, and the “Fitness” Snag

- Memetics Pt. 2: The Four Brothers (and Their Business Booths)

- Memetics Pt. 3: The Short Tower Problem

- Memetics Pt. 4: Short Towers + Secret Gnosis

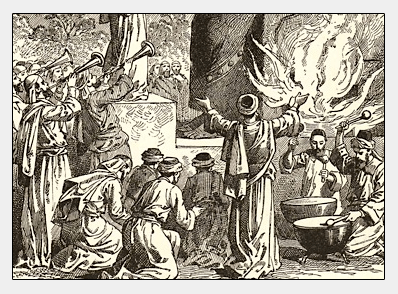

Kicking Baal Out of Schools

You live in the United States. In the Constitution, it says that congress can make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.

One of the founding fathers, Thomas Jefferson, described this amendment as a “wall of separation between the church and the state.”

You go to a state-run public school, which must conform to this Constitutional maxim.

First Day of School

It’s your first day at this school, having arrived in a new town after moving.

You get on the bus and are driven to school. The bus parks, but the door hasn’t opened yet. The bus driver is sitting there, silent.

A student in the very front stands up. She is wearing a strange conical hat.

“All who worship Baal Hadad as master and lord, raise your hand in reverence!” she shouts. All of the other children raise their hands and look around.

Several notice that you’re not raising your hand, and begin to whisper and murmur to one another. Soon, everyone is talking about you, and looking at you like something is completely wrong with you.

You really want to leave. Why isn’t the bus driver opening the door? You stand up and walk hurriedly down the aisle.

“Let me off,” you shout at the bus driver.

“Of course, you’re not captive,” says the driver, and opens the door for you.

But Soon…

You go to your first class. The bell rings for class to start, but the teacher is sitting silently at her desk, reading.

Like on the bus before, a student up front, wearing a conical hat, stands up and addresses the students.

“Let us now sing praises to Baal Hadad, king of the heavens!” he shouts.

He begins to sing. The other students join him. You don’t want to be a part of this.

You get up to walk to the teacher, who is still reading silently. As you do, the other students stop singing, and stare, aghast that you would interrupt the worship. They give you horrible looks and scoff.

You ask the teacher to be excused.

“Of course,” the teacher says, and gives you a pass to read in the library until the lesson begins.

You come back 10 minutes later, and the teacher has already started teaching. You rush to take your seat.

This happens in several subsequent classes. Sometimes singing, sometimes a creed recital, sometimes a prayer, sometimes a “meditative moment of silence.”

Similar things happen at lunch.

You go to an assembly. Same thing.

Each time, no school faculty is directly involved. They just sit silently while the students lead the Baal-worship. And each time, when you ask to be excused, you’re allowed.

Legal Action

This is a horrible state of affairs that clearly violates that “wall of separation” of which the Jefferson wrote. This town of Baal-worshipers is transparently and cynically incorporating Baal-worship into their public school system by using a “back door” of “periods of inactivity” + “student-prompted actions.”

You decide to hire a lawyer and try to put a stop to this.

The resolution is that if public school faculty has reasonable knowledge that a student plans to perform religious rituals for reasons other than pure, curricula-driven education, they have to stop it. Otherwise, they are giving official permission, even if it’s veiled under the auspices of “faculty passivity” and “student freedom.”

The Supreme Court hands down this decision.

To violate this decision is to violate the Constitution.

The Social Aftermath

The incorporation of prayers and worship and creeds to Baal disappears at your school.

Now, instead of getting dirty looks from students for asking to be excused, you get dirty looks from students and their parents.

They blame you for “kicking Baal out of schools” and falsely complain that the school has “banned prayer.”

Conclusion

State-run institutions should not be complicit in the worship of deities, because not everyone believes in those deities.

As Christians, we should be passionate about making sure that everyone is treated with charity and equity, and not attempt to force our beliefs on others through state-run institutions.

Prideful shows of allegiance, intimidating social pressure, and ostracism do nothing but sow resentment and discomfort in non-believers. This is trivially obvious when you craft an imaginary situation in which you’re in “their shoes.”

Memetics Pt. 3: The Short Tower Problem

In the last two videos on memetics (see schedule below), we talked about how truth — and other things we like — may not be decisive when it comes to the “spreadiness” and “stickiness” of certain ideas. In other words, “goodness” does not necessarily yield “fitness.”

But that’s not the whole picture. Vital to memetics is an understanding of how neuropsychological patterns can prompt and prevent virulence and resilience (“spreadiness” and “stickiness”).

Today, we’re going to talk about one of the most important patterns to understand — loss aversion — and how it impacts memetics.

We’ve already talked about loss aversion twice on this site:

- In “Bibliopsychology: Why the Servant Did Nothing,” we talked about the reluctance to commit our charity, a failing against which we must fight.

- In “Up a Tree,” we talked about a good way to think about loss aversive rooting behavior. Today’s video will echo some of these themes.

Its impact on memetics is manifold, and I think you’ll enjoy how the breakdown plays out through the story of the tower seeker.

(For those familiar with genetic algorithms, this is “local maxima” in function.)

Get out there and really investigate. I can’t believe this guy when he says, “I’m an authority,” “I’m Dr. Tower (even if he is Dr. Tower),” “They have a conspiracy”… These things might all be the case, but you are the final gatekeeper to the keep of what you believe.

Schedule

- Memetics Pt. 1: Introduction, and the “Fitness” Snag

- Memetics Pt. 2: The Four Brothers (and Their Business Booths)

- Memetics Pt. 3: The Short Tower Problem

- Memetics Pt. 4: Short Towers + Secret Gnosis

Memetics Pt. 2: The Four Brothers (and Their Business Booths)

In the first of our four-part series on memetics, we talked about how the virulence (“spread-iness”) and resilience (“stickiness”) of ideas determines the flourishing of those ideas, even if those ideas are bad in terms of things we call “goodness,” like truth, justice, and quality of life.

This has the counterintuitive result of labeling really bad things as “fit.”

Today, we’re going to apply this to a thought experiment in which four brothers try to make their businesses successful through four different strategies.

First, we’ll meet Reilly, Murtagh, Shane, and Lochlan.

Later in the video, we’ll also be introduced to a fifth (bonus!) brother, Gerrard, and see what strategy he employs, and how it works out for him.

The illustration of the brethren and their booths will demonstrate how:

… memetic action — resilience and virulence — is what matters [for flourishing]. Truth kinda goes by the wayside. Making sense can kinda go by the wayside. And if you and I care about truth and making sense — which I’m sure we do — then we’ve gotta watch out…

Schedule

- Memetics Pt. 1: Introduction, and the “Fitness” Snag

- Memetics Pt. 2: The Four Brothers (and Their Business Booths)

- Memetics Pt. 3: The Short Tower Problem

- Memetics Pt. 4: Short Towers + Secret Gnosis

Memetics Pt. 1: Introduction, and the “Fitness” Snag

Evolutionary patterns can be applied, by analogy, to anything that has similar basic mechanics of virulence (“spread-iness”) and resilience (“stickiness”).

Those basic mechanics aren’t that big of a deal and aren’t controversial. If something spreads and sticks, passing various selective “tests,” it has a better chance to flourish.

We take advantage of this fact when we utilize genetic algorithms in software. The software isn’t dealing with real organisms, cells, or DNA, but we don’t need those things — we just need mechanics analogous to those basic evolutionary principles.

Over the last few decades, we’ve all started to recognize that social information has mechanics analogous to these basic evolutionary principles.

Again, this shouldn’t really be controversial — obviously, some ideas are better than others at spread-iness and stickiness, and are tested against various selective agents in the environment.

This is important to recognize, however, because the various conceptual snags and counterintuitive patterns we recognize in genetic evolution can help us power past conceptual snags and counterintuitive patterns that have been infecting theology, philosophy, and any other social collection of ideas.

In the church, this bears itself out in:

- Doctrinal disputes

- Persistent error or incoherence

- Tribal bickering and quarreling

- And much, much more

The following is the first in a four-part series of a basic introduction to memetics, and how it affects philosophy and theology.

At 7:25:

So here’s the weird thing. You can have a genotype that has great virulence and resilience, but is bad in terms of things [of which we] say, ‘We think this thing is good.’

For instance, it might be bad for justice, it might be bad for truth, it might be bad for quality of life, it might be bad for all of these things — but because it is high in virulence and resilience, it wins.

It dominates the environment over time.

Ugh! That’s lame!

Schedule

“Omniscient Prole” Dilemmas

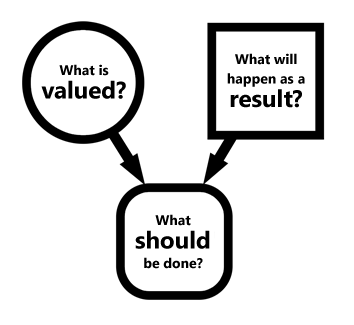

In pure consequentialism, an act is morally right if it produces results that represent an optimization of what is valued (whatever that is).

All statements of “should” or “ought” are built from two inputs:

- “What is valued?,” i.e., “What is the goal, interest, or desire (or set thereof) to which I’m acting in service?” and

- “For each prospective course of action, what will happen as a result?”

So we have our circles (input values or goals) and our squares (how things work). These always resolve into rounded rectangles (moral statements under consequentialism, e.g., “It is right to do X,” “I should do X,” “X is justified,” “X is correct,” “X is praiseworthy,” “Y is wrong,” “Y is suboptimal,” etc.).

Our Problem: We Are Numbskulls

The thing is, our squares are ill-defined. We may never have perfect squares because observations about the mechanics of the world, in general and in specific instances, may never be completely accurate.

And because the world is chaotic (that is, rather orderly, but nonetheless incalculably complicated), our faculties of foresight are dramatically limited.

We can’t even predict the weather accurately more than 3 days out. How much more terrible are we at predicting the effects of our actions on human behavior, including our own behavior?

We not only recognize that we don’t know that much about how the world works, but we simultaneously recognize that this ignorance leads to unintended consequences all the time.

We respect this intuitively, and we account for it in our decisionmaking.

Our Solution: Humility and Recognition of Uncertainty

Just as businesses account for risk in their decisionmaking, we individuals make intuitive attempts at accounting for risk. We recognize that our squares are severely crippled, and so many of our “shoulds” are loaded with qualifiers like “probably” and “maybe.”

For this reason, we say that pure consequentialism is impractical. We adopt some diluted form of consequentialism that recognizes our imperfect understanding of the world and the dramatic impact that imperfection has on our ability to predict the full consequences of our actions.

This includes even moral templates that allow for rules; it allows us to say that blanket, imperfect social laws may sometimes and in some places be required to correct for subjective error and individual stupidity.

So even as consequentialists, we reject pure consequentialism on the grounds that we are dummies. We humble ourselves below the status of omniscient beings because we know we aren’t.

See this post for an introduction to this concept, called “The Angelic Ladder.” We are “Near-Proles”; we are not completely stupid and blind to consequences, but we are pretty stupid, and pretty blind to consequences.

Loaded Moral Dilemmas

So, here’s the trick that many thought experiments pull:

- They set up a situation that tests your decisionmaking in a consequential context.

- They then give you some measure of implausible omniscience, e.g., “You know for absolute certain that pushing the fat man in front of the train will derail it, and that the train is certainly empty, and that the derailed train will not hurt the group of people you’re trying to save.”

- They then watch as you squirm with the anxiety of being an “omniscient prole,” where you’re struggling to reconcile your learned, intuitive, hammered-in humility with the new God-power you’ve been granted by the situation.

The thought experiment wants you to think that it’s demonstrating that consequentialism is an incomplete description of morality and needs additional deontological (“morality is all about rules”) magic. But all it’s actually doing is showing that we are intuitively averse to pure consequentialism because we know we’re so limited.

In other words, morality isn’t some same-level hybrid of consequentialism and deontology. That’s something a lot of people think and something with which a lot of people struggle.

Rather, morality is consequential, but due to our limited faculties of foresight and understanding, we find it useful to employ bits of subordinate deontology.

I’ll again link you to the previous post on the subject, “The Angelic Ladder,” which serves as a primer to “rules under consequentialism.”

Dealing with Loadedness

If someone asks you, “Are you a piece of garbage, or do you just smell like one?,” how should you respond? No, don’t punch them in the face. Rather, choose one of the following options:

- Indict the loadedness. “That’s a loaded question so I refuse to respond.”

- Unload the question. “I am neither a piece of garbage, nor do I smell like one.”

Similarly, if someone gives you a moral dilemma loaded with implausible omniscience, either are fine:

- Indict the loadedness. “That situation gives me implausible omniscience which ungrounds us completely, so I’m not going to respond as if my answer would reveal anything morally significant.”

- Unload the situation. “I wouldn’t fathom that the man’s body would be able to derail the train, would worry that the train would contain passengers I’d put at risk, and would be concerned that a derailed train might hurt the very group I’d like to save. Sorry. Real situations are addled with uncertainty.”

(It so happens that if we’re dealing with a moral situation with low uncertainty and non-competing interests, then the more grounded that moral dilemma is, the easier it is to answer confidently.)

Logical Wildcards

Let’s say you think you’re playing Five Card Draw, no wilds. You ship some cards and get some back, and end up with a measly pair of deuces.

This isn’t looking so hot. You’ve been bluffing a great hand this round, and don’t have the goods to back it up.

“Oh, we forgot to tell you,” says your friend Harriet, “Bernice is dealer and — while you were in the kitchen — called this round as deuces wild.”

What? Deuces wild? Just as you’re about to complain that the whole round was contaminated, you suddenly realize that with deuces wild, you have a royal flush!

The Utility of Wildcards

Wildcards are extremely useful. They can turn weak hands into kingmakers. They can turn low pairs into royal flushes.

Their power is that they don’t mean anything discrete and coherent unless and until they’re integrated into a final, optimal hand resolution. At that moment, they mutate and solidify into whatever the player pleases.

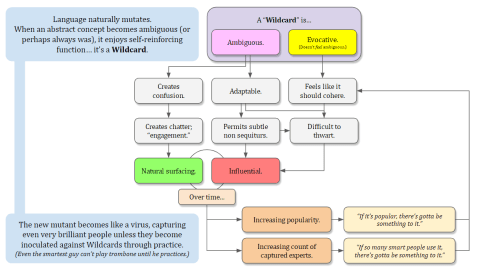

There is an analogous object, with analogous utility, in logic and rhetoric. Any claim that has no discrete and articulable truth value can qualify, and there are many ways that a claim can be “amorphous” in this manner.

- A claim may be many-faced. “My car is pleasing.” Well, what does that mean? Jake could call his car pleasing, when it doesn’t even work, but looks nice in his driveway. Vera could call her car pleasing, when it looks like junk, but performs great on the road.

– - A claim may be nonsensical. “My house is a thing against which there house is no house my house isn’t my house in transcendence, cannot it being.” The preceding sentence probably invokes various images in your mind’s eye, but it does not cohere, and thus can’t have a truth value.

– - A claim may be otherwise vague, unclear, ambiguous, or wide open to interpretation.

– - A claim may have a hidden referent. The many-faced example above is also a good example here. If the referent is explicated (what pleases Jake versus what pleases Vera), it can cohere. But as long as the question is without its necessary referent, it lacks a truth value. Subjective claims that are mistakenly put into objective language are very often guilty of this referent-lacking problem.

If any of these problems are present and yet are undetected, and treated like coherent and solid claims with discernible truth values, they can mutate and solidify around whatever the hand-holder desires.

Bridge-Making

Cheryl is late to my party, and I’m worried that she might be lost. In a misguided effort to comfort me, Brent claims the following:

- “Cheryl is flawless at finding a house if she knows its address.

- Thus, Cheryl is not lost.”

Of course, at this point, I think, “But what if she doesn’t know my address?” Brent suspects I might be thinking this, but doesn’t himself know whether she has my address or not. So he tells me something deliberately vague:

- “Cheryl has quasi-panomic knowledge.”

What does that even mean? Further inquiry yields only more such strange statements from Brent, each more unclear than the last, but all in supposed service of clarifying that odd term.

He hopes that I will eventually give up and accept his statement as a bridge. This happens when the images conjured by what he’s saying — a sense of “knowledge” and “full,” at least — come to a rest at some inferred coherent place, like, “She has my address.”

But I refuse to quit, and shout, “Brent! Does she have my address or not?”

“I’m trying to tell you the answer to that!” he says, “You see…” and then continues with the ambiguity.

Now, instead of coming to rest at something vaguely conjured, I can instead say, “Brent, what you’re saying is not cohering. So while it might express some manner of truth, I can’t use it as a premise in service of any conclusion.”

Bridge-Breaking

Soon, Brent appears to be drunk. “How many drinks have you had, Brent?” I say.

“Eight,” he says.

“In an hour??” I say.

“Yeah,” he answers.

“You’re drunk,” I proclaim.

“No I’m not! I’ve got a just-firm and nigh-set constitution,” he says.

“A ‘just-firm and nigh-set constitution?'” I ask.

“Absolutely,” he responds. “It means that eight drinks in an hour does NOT mean that I’m drunk. Such a thing would be unthinkable.”

I press him for a more dissected meaning of “just-firm and nigh-set constitution,” in order to determine whether he “has that,” whatever it is, but only ambiguity and dangling references (like circular references) come forth.

How on Earth can I determine whether he has the thing that invalidates my conclusion when the thing’s definition is “that which invalidates your conclusion” and nothing more?

Now, instead of coming to rest at the vaguely-conjured image of someone exceptionally tough who can hold a lot of alcohol without issue, I can instead say, “Brent, what you’re saying is not cohering. So while it might express some manner of truth, I can’t use it as a premise that would stop the accepted premises — how many drinks you’ve had in this period of time — from yielding the conclusion that you’re drunk.”

Brents Everywhere

These examples are rather silly, but in the abstract and confusing worlds of philosophy and theology, Brents abound.

And they’re incentivized to proliferate! Wildcard-loaded hands are “better.” And confusion, “subjective-as-objective,” and ambiguity all yield exciting conversations in fruitless attempts to reach cohesion.

This is especially the case in theology, where it is accepted and acknowledged that various revelatory statements are mysterious and beyond our comprehension. The error comes when those mysteries are treated as non-mysteries for the purposes of bridge-making and bridge-breaking.

As believers, we hold to revealed mysteries faithfully. But we should regard them with enough humble reverence not to treat them like pilons or sledgehammers.

In the meantime, if someone employs some strange term as a premise and refuses to articulate it in a coherent way, treat that term like it’s toxic glowing green and reject their logic until they take a break and figure out what they’re trying to say.

Bonus Video

This video, called “The Difficult Ds we Get for Free,” talks about how formal logic gets us “free truth” as corollaries of benign premises, but how the “dirty tricks” of ambiguity can be used as logical wildcards.

Bonus Illustrations

Logical wildcards can take on a life of their own as organism-like “memeplexes.” Their power compounds as they turn heuristics we depend upon (popularity & experts) into carriers by “capturing” them.

This happens very often with pejorative terms, which are useful as adaptable scapegoats or boogeymen. Common pejorative wildcards in Christian discussions include “Gnosticism,” “semi-Pelagianism,” “neo-Marxism,” “socialism,” “postmodernism,” “fundamentalism,” and “works salvation.”

However, it also happens with positive terms like “freedom,” “moral,” “rational,” “objective,” “Biblical,” and “Christian worldview,” through which a group’s partisan perspective can be smuggled:

Recent Comments